‘I’m Still Here’ is inspired by the ‘disappearance’ of a real-life congressman in Seventies Brazil, and directed by Walter Salles, a childhood friend of the congressman’s family. It’s just the latest in a strange sub-genre of historical fiction made by filmmakers with insider access, writes Xan Brooks – for better and for worse. History comes to the living room,” said the author Philip Roth, summing up the ideal of all historical fiction, which is to show how big events impact daily lives and real people. Roth was specifically talking about his own later novels (American Pastoral; I Married a Communist) but his description applies just as easily to I’m Still Here, an outside bet to scoop this year’s Best International Feature Oscar. Directed by Walter Salles, the veteran Brazilian filmmaker behind Central Station and The Motorcycle Diaries, it spins the tale of the true-life Paiva family whose happy, middle-class existence is upended by the country’s military dictatorship. In this case, it transpires, history comes not only to the living room but the downstairs hall, the kitchen and the kids’ bedrooms as well.

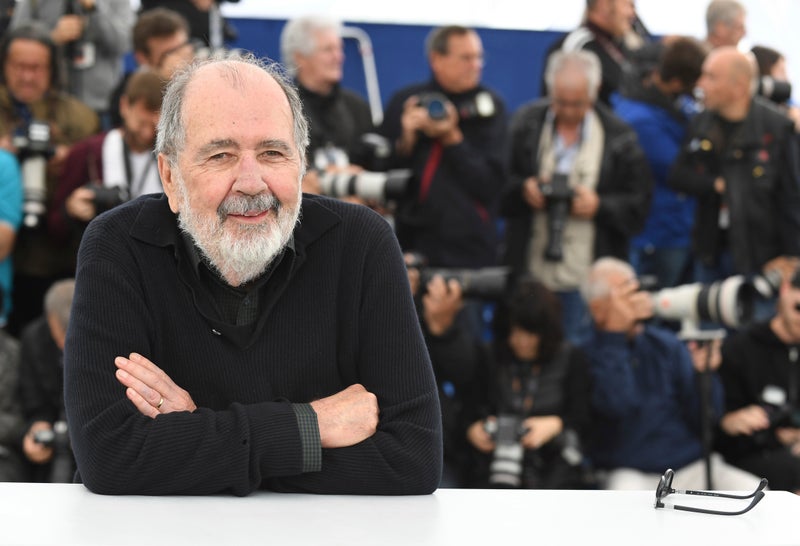

Salles’s drama is adapted from a book by Marcelo Paiva, the family’s eldest son. But it’s also based on the director’s first-hand experience. Salles knew the Paivas as a child, was a frequent guest at the Paivas’ home and credits the family with providing his political education. So he’s recreated their Rio beachfront house exactly as he remembers it and approaches their story with the care and compassion one would expect of a trusted friend and confidante. His film’s an insider’s account, the equivalent of embedded journalism, and is all the better – and the worse – for that.

The family’s ordeal is a matter of record. Rubens Paiva was a liberal former congressman, active in the underground opposition, who was abruptly “disappeared” by the authorities in January 1971. Salles’s proximity to the material, though, enables him to add crucial texture to the bald case study, showing the ways by which state-sponsored oppression is perpetrated by low-level functionaries who don’t quite know where to put themselves. The film’s central abduction scene is brilliantly done, lifted straight from life. The oblivious kids continue with their game. The mother, Eunice (an Oscar-nominated Fernanda Torres) awkwardly offers to fix the goons some lunch. Evil, it suggests, isn’t always a monster that’s come to kick down your front door. More often it sidles in with a sheepish air that leaves its victims nonplussed and unaware they’re in danger.

Brazil’s two decades of military rule are still recent enough that the period remains a live issue, not yet put to bed. As such, I’m Still Here is a South American political drama that takes its place alongside Marco Bechis’s Argentinian-set Garage Olimpo or Pablo Larrain’s Tony Manero, a pitch-black satire of daily life in Pinochet-era Chile. But Salles’s personal connection to the Paivas also makes the film part of a wider, more eccentric tradition in which the tale itself becomes a feedback loop, coloured by the maker’s own memory and his relationship to his characters. I’m Still Here provides a Brazilian history lesson of sorts, but it’s partial and subjective, more akin to a memoir than a dispassionate re-enactment.

Latin America excels at this school of storytelling: the close-knit of the recent past with the present; the artist with his clay. Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Dance of Reality, for instance, is a gloriously bonkers autobiographical drama that delights in placing us in the thick of the action. The Chilean director doesn’t simply cast his own son, Brontis, as his brutish dad; he also appears on-screen at intervals to comfort the boy who plays his younger self. More extreme still is the case of The Life of General Villa, a 1914 silent movie that was shot against the backdrop of the Mexican civil war. Real-life battles were coordinated in advance with the film’s production crew. The title role was performed by none other than Pancho Villa himself. Pull too close to your subject and the line between fact and fiction can’t help but break down. Villa’s film is not a re-enactment; it's not even a memoir. It sounds alarmingly like the world’s first reality show.

The complete print of The Life of General Villa has long since been lost, which means we can never know how good Pancho Villa was at playing Pancho Villa. But let’s assume that he was at least as convincing as Prince was in Purple Rain, or Eminem in 8 Mile or Tommy Steele in The Tommy Steele Story, which is to say that he was entirely serviceable playing a version of himself. That might please the fans; it doesn’t make for good history. Real people, god bless them, aren’t always great actors, just as privileged access doesn’t guarantee a great film. Was Mario Van Peebles the best man to write, direct and star in a movie (2003’s Baadasssss!) about his filmmaker dad, Melvin? Was Julian Schnabel the right choice to make a biopic about his friend, Jean-Michel Basquiat? The response in both cases would suggest otherwise.