Exclusive: The bloody foundering of President Gustavo Petro’s ‘Total Peace’ strategy is a ‘national failure’, says Juan Manuel Santos, who ended war with Farc guerrillas in 2016. Colombia risks sliding back into its violent past as armed groups exploit the stumbling peace strategy of President Gustavo Petro, the architect of its landmark 2016 peace deal has told the Guardian.

![[Juan Manuel Santos.]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/ee5891620514dfbcc517d06cec1346959d8d9b79/692_0_2116_2645/master/2116.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

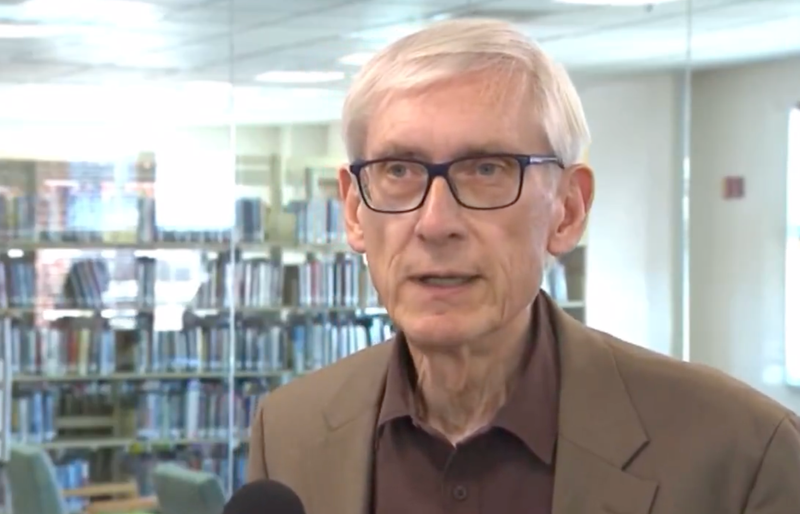

In a rare interview, former president Juan Manuel Santos warned that gains from the peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) are quickly being undone as armed factions exploit negotiation efforts to recruit new combatants and seize control of new land.

![[A security official works in the area where several bombs exploded on a highway tollway on the Colombian-Venezuelan border between Cúcuta and San Antonio del Táchira last week.]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/f10eceb6621cf75bfbf67929c030ccd03ab88cbc/0_56_1682_1010/master/1682.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

“I’m seriously concerned about the deteriorating security situation and how armed groups are growing. They are taking advantage of the government’s disorder to strengthen themselves, fight amongst themselves and take more territory,” he said. Santos’s peace deal with the Farc – at the time, the most powerful guerrilla insurgency in the western hemisphere – led to 7,000 combatants laying down their rifles and gave Colombians the hope of a more peaceful chapter in their country’s bloody history.

![[President Gustavo Petro holds a ceremony to formally begin a six-month ceasefire with the National Liberation Army (ELN) in Bogotá on 3 August 2023.]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/9fd01ce5c8e0fa4d9fa9b01ce272fb395142cab8/0_122_3671_2203/master/3671.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

The following year was the least violent in five decades but Santos’s conservative successor, Iván Duque – who campaigned on a promise to kill off the peace process – refused to implement the accord’s agreements. Since then, dozens of new groups have sprung up to fill territory once controlled by the Farc and are warring with each other to control the cocaine trade, illegal mining and extortion rackets.

![[President Juan Manuel Santos, left, and Timoleón Jiménez, the top leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc), exchange pacts while the Cuban president, Raúl Castro, in Havana on 23 June 2016.]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/e49cfbece42f68c310813374eb141742230d6f3f/29_113_2969_1781/master/2969.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

A handful of groups have retained elements of revolutionary ideology but most are little more than local mafias. When he was elected in 2022, Petro – Colombia’s first ever leftwing leader and a former urban guerrilla himself – pledged to launch talks with every major armed group as part of his “Total Peace” strategy.

But negotiations have yielded little progress and the government has been repeatedly forced to break off talks as rebels refuse to stop kidnapping and killing civilians. In the past two months, Colombia has seen a wave of violence across the country, from the far southern state of Amazonas to the Pacific coast.

The worst of the violence has been concentrated near the north-eastern border with Venezuela, where Colombia’s largest armed group, the National Liberation Army (ELN) launched an offensive in January that has killed at least 80 people and displaced 85,000.

Last week a million people in the border city Cúcuta were put under curfew after ELN fighters attacked police stations and toll booths with car bombs and machine guns. “We thought Petro was going to correct course. He promised that in the campaign, but he has not delivered. We are now worse off than we were two and a half years ago,” said Santos.

Analysts warn that armed groups are growing unchecked in the Colombia countryside as the military, confused by the government’s stop-start efforts to negotiate with each group separately, is unable to hatch an effective strategy to combat them. Kidnapping has increased 79% since Petro came into office, child recruitment has increased 1,000% in the past four years and data from Colombia’s human rights ombudsman shows that criminal groups are seizing territory quicker than they were under Duque.

Petro broke off talks with the ELN on 17 January, and contacts with all other major groups have also either been terminated or suspended. Only one ceasefire, with a dissident Farc faction, remains active. But although he has described the recent bloodshed as a “national failure”, Petro has insisted he will not drop the Total Peace strategy – even as members of his own cabinet have publicly asked if the peace process is unravelling.

Santos said that negotiating with armed groups requires tact, extensive research and planning, but Petro’s strategy appears to have been improvised. “You need to know what your objectives are. You need to know what your red lines are. And you need to know what you want to achieve. None of that was present. It was improvised, there was no planning and they had no idea who they were negotiating with,” he said.

Santos said he warned Petro’s team that its ambitions to convince more than a dozen armed groups to disarm simultaneously were overly optimistic; it took four years to negotiate a deal with the Farc – which although it had more than 13,000 members had a clear top-down structure and hierarchy.

“I told them: ‘You might be Superman, you might be the most intelligent person in the world, but if you think you are able to negotiate with 14 different groups at the same time that would be a failure.’ And that is what has happened.”. And with each ceasefire, as the military eased off pressure, the armed groups have taken advantage to recruit new members and expand their control.