The Swedish chef is reviving ancient techniques, ditching modern kitchens and embracing the raw power of open flames. At his London restaurant, that means flambadou-fired oysters, juniper-smoked beef and a history lesson in every bite, writes Lauren Taylor.

![[Oysters are flambadou-fired, dripping with molten beef fat for a rich, smoky finish]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/02/12/11/12101211-4695b9a6-3114-4737-87f6-1227ca578ca1.jpg)

Head chef Luca Mastrantoni sends a long stick with a metal cone filled with dry-aged beef fat into a roaring open fire, setting the whole thing alight, before hovering it over the oyster I’m about to eat. What’s known as “flambadou” is an ancient Swedish cooking technique, used by the indigenous Sámi people of the north of the country, and revived by chef patron Niklas Ekstedt. It gives the oyster a unique rich finish, served alongside beurre blanc here at his UK restaurant Ekstedt at The Yard.

![[Niklas Ekstedt outside Ekstedt at The Yard, his restaurant in Great Scotland Yard]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/02/12/11/12105647-441eb5dc-02cc-4f7a-8aec-a1ec6e0a3fdc.jpg)

“I found [the device] in an drawing in an old book,” explains Ekstedt. “We heat it up until it’s very, very hot, then we light the fat and everything almost explodes, and the fat drips down to whatever we’re cooking.”. Today, Sámi communities inhabit parts of Sweden, Norway, Finland and Russia and in Sweden many live in Swedish lapland as nomads, most travelling with reindeer herds.

![[The finished dish: oysters served with beurre blanc, showcasing Ekstedt’s signature fire-cooked flavours]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/02/12/11/12101643-a0697854-4c04-4405-9b5b-a86712da6cfb.jpg)

“It’s a history and a legacy that not that a lot of people know about in Europe,” says Ekstedt. “Their food is very based on being out on the mountain. They have long times without so it’s either a dish that’s cooked very quickly on the fire, like the heart or the blood, and eaten immediately, or it’s meat that’s very thick, dried and either smoked or salted heavily.”.

![[Open-fire cooking in action – Ekstedt’s kitchen runs on flames, embers and centuries-old techniques]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/02/12/11/12101819-ea815909-944a-4186-bdf7-ca45d6908ac3.jpg)

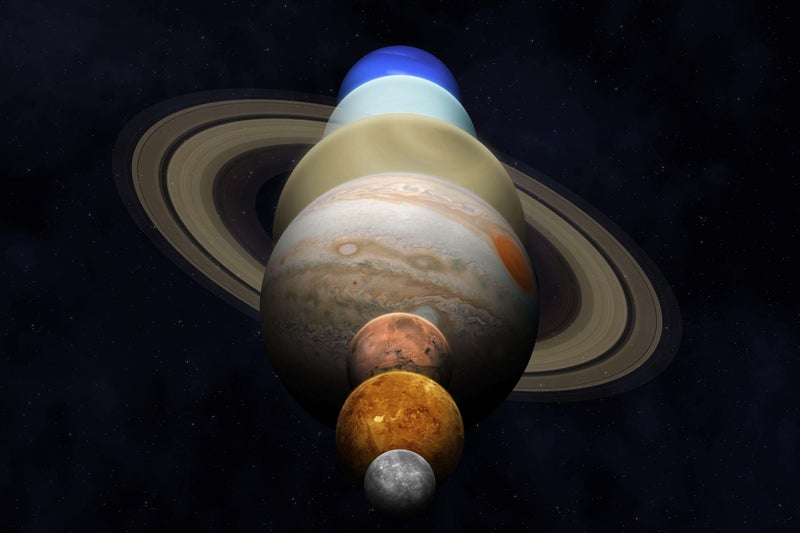

Inspired by the indigenous communities and the forests and mountains where he grew up in Åre, Jämtland, the 46-year-old chef has made a name for himself taking food preparation back to its most primitive – using fire only. Head to his one Michelin star Stockholm restaurant and you’ll find a professional fine dining kitchen with absolutely no electricity or gas.

Based on birch wood and cast iron, the same principles are used in London – but being in a hotel, you’ll have to forgive some modernities like lights in the kitchen. Here he uses British, mostly Scottish, ingredients alongside old Swedish techniques; think birch fired scallop with ember butter, juniper smoked sirloin of beef and hay smoked pork loin.

Ekstedt was part of the “new Nordic cooking” revolution around 20 years ago, alongside the likes of Noma’s René Redzepi, when top Scandinavian chefs turned their attention to the ingredients available around them. “It used to be that fine dining restaurant food was either French or Italian or Chinese, even in Sweden, we didn’t cook Swedish food in restaurants – it was something you ate at home,” he says.

“We started sourcing from northern Europe, having fresh local produce, skipping foie gras [from France] and caviar from Russia. It was a beautiful way of thinking, changing the idea of what food can be.”. After working in Chicago’s famous Charlie Trotter’s and Spain’s El Bulli, Ekstedt returned home to set up his own restaurant at the age of 21 (“a cliche Michelin restaurant with purees and white tablecloths,” he laughs) at the height of new Nordic movement – and was touted as Sweden’s Jamie Oliver.

“When I went on Swedish TV and became and a celebrity chef in Sweden, I decided to quit,” he says, deadpan. “I didn’t want to be a celebrity. I wanted to be famous for my cooking and my handicraft. I sold my restaurants and quit all my contracts.” He spent a year off looking after his first son (as is tradition in Sweden when mothers go back to work) after buying a house on the Stolkholm archipelago.

“I had this romantic idea of just chopping wood,” he says, but instead, it gave him time to rethink what was important and he started learning about old cooking techniques forgotten in history. Sweden boomed after the Second World War; “We went from the poorest country in Europe to the richest in under 100 years. People threw out all their historical cooking gadgets. Italy are still cooking pizza in a wood oven, in India they still use the tandoori oven, but all Scandinavian historical food had been erased. My mother never learned from her mother how to cook Swedish food.”.

Unearthing it became an “historical assignment” for him. “I had to literally go to the library and start reading and researching about it. And it was just amazing because I found so many gadgets and so many techniques that were forgotten and that were incredible in so many ways.

“I didn’t even know what they were or how to use them – no one was using them.”. Further inspired by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl, who wanted to prove that “old civilizations were way smarter than we think today”, he opened Stokholm’s Ekstedt in 2011. The reception was “not great” he laughs, despite gaining a Michelin star two years later. “It was struggling in the beginning, quite a lot.

“The biggest challenge was to get cooks and chefs to do it. A lot of chefs liked the idea but when they came and lived the practicality [of cooking with only a wood fire oven, hot bricks and a fire pit] they’re like, ‘I have no use for all these things that I’ve learned!’. Like the romantic idea of sailing over the Atlantic, and then you’re sitting in the middle of the [ocean] and you don’t have an engine.”.