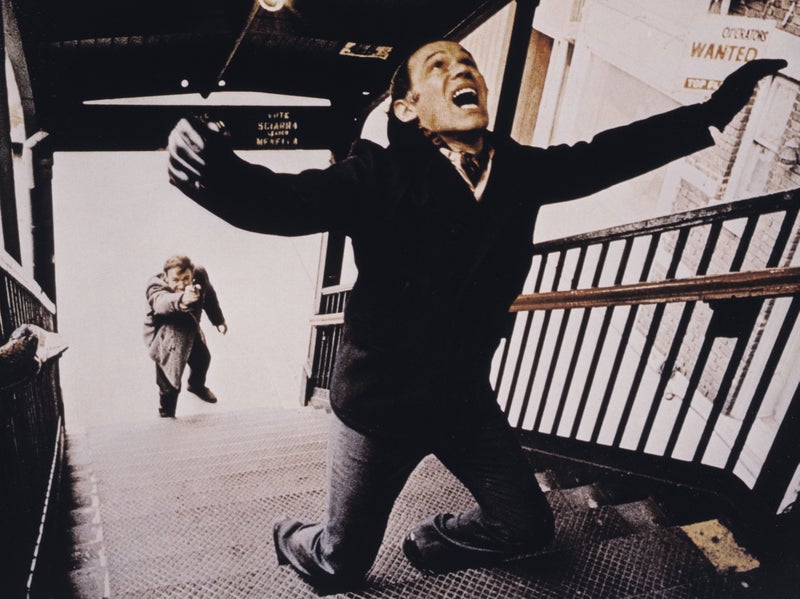

More than half a century after William Friedkin’s revolutionary action film stunned viewers, Geoffrey Macnab looks at how the rogue cop at its centre manages to be so perversely sympathetic. It’s the dead of winter. As Santa Claus rings his bells on a pavement in Brooklyn, a hot dog vendor wanders into a bar. That’s when the commotion begins. A drug dealer with a knife bursts out of the door. Santa and the vendor both try to stop him but he scarpers. They chase him down the street, eventually catch him on a patch of wasteland and gleefully beat him up.

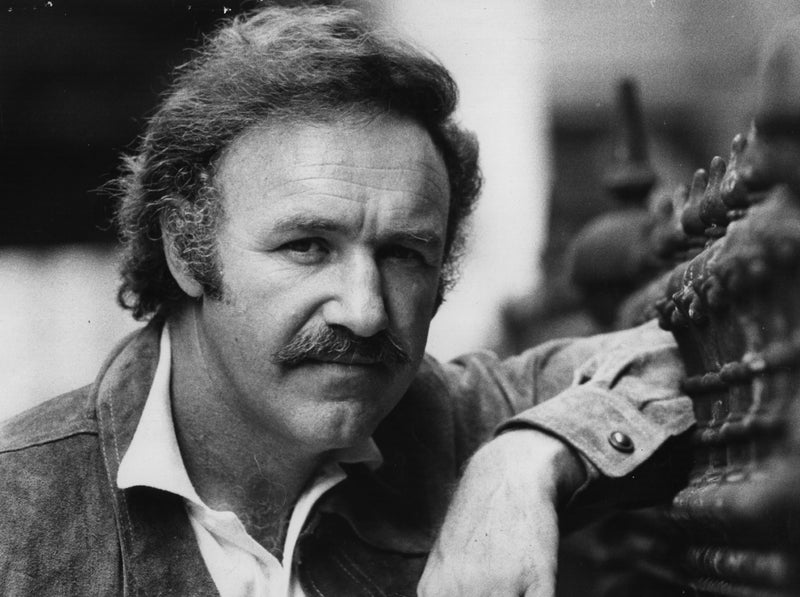

This is how we encounter Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle (Gene Hackman) in William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971). He may be dressed as Father Christmas but he is an undercover cop with a volcanic temper. The fast food seller is his detective partner, Buddy “Cloudy” Russo (Roy Scheider).

Movie protagonists rarely seem so obnoxious at first sight. Popeye is violent, impulsive, possibly racist and doesn’t care at all for the kids he is pretending to entertain. He’s a pug-faced curmudgeon with an alcohol problem and he is a bad Santa to boot. It is not even clear he is an effective cop. He works on intuition but his “brilliant hunches” continually backfire.

Hackman found the character so repellent that (according to biographer Michael Munn) he briefly threatened to quit the movie. It didn’t help Hackman’s mood that director Friedkin shot multiple takes showing the drug dealer (Alan Weeks) being beaten up. “I felt horrible,” Hackman later said, remembering when he repeatedly punched his co-star. Weeks reportedly took the blows (which were very real) in good heart, smiled through them and told Hackman to carry on hitting him.

Half a century ago, when The French Connection was first released, it was considered revolutionary precisely because it was so old fashioned. This wasn’t a counter-culture drama with psychedelic references like Easy Rider (1969) and Head (1968). Nor was it was one of those movies about outsiders chafing against mainstream society like Five Easy Pieces (1970) and Midnight Cowboy (1969). It was a hard-boiled cop thriller shot in dirty realist fashion. There were no mind-bending special effects. The film’s main visual highlights are chases, either in cars or on the subway. Hackman’s rough-hewn quality was perfect for the mood Friedkin was setting. Cinematographer Owen Roizman used natural light wherever possible but, other than in the French-set scenes, there is not a peep of sunshine. Everything is deliberately grey. The streets are strewn with rubbish and graffiti. The famous final set-piece takes place in a derelict old industrial building, with leaking roofs and rubble as a backdrop.

Steve McQueen had been the producer’s first choice as the lead star, but he turned The French Connection down on the grounds it was too close to Peter Yates’ Bullitt (1968) in which he had appeared a couple of years before. McQueen might have made an excellent Popeye but he was among the coolest, best-looking actors of his era. Hackman, by his own admission, was far from handsome.

It’s strange, though, the way that cinemagoers’ sympathies work. From the first moment they see him, almost everybody roots for Popeye. Hackman plays him with a long-suffering stoical dignity that verges on the comic. It’s as if he expects the worst. If he goes drinking, he’ll wake up with a hangover. When someone starts shooting at him or a girlfriend chains him to the bed after sex or Fernando Rey’s dapper French villain gives him the slip yet again, he’ll always react in the same fatalistic, hangdog way. His porkpie hat gives him a cartoonish quality. Somehow, against considerable odds, the rogue cop comes across as perversely sympathetic.

The film is based on the true story of two celebrated New York cops, Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, who, in 1961, had made a spectacular drugs bust. Both have roles in the film. It’s instructive to watch old interviews with the duo. As they wax nostalgic about the good old days of the 1960s when they could freely arrest, bully and harass anyone they wanted, without having to go to the inconvenience of reading suspects their rights, they look and sound exactly like Hollywood’s favoured version of big city detectives. They’re tough, charismatic and reactionary. You could put them in an episode of The Wire or in an old Sidney Lumet film about police corruption and they would fit perfectly.

Friedkin is quoted in Easy Riders Raging Bulls (Peter Biskind’s book about Hollywood in the 1970s) as having been inspired to make The French Connection by a remark from legendary filmmaker Howard Hawks. “People don’t want stories about somebody’s problems or any of that psychological s***. What they want is action stories. Every time I made a film like that, with a lotta good guys against bad guys, it had a lotta success,” Hawks told Friedkin. This was a moment of epiphany for the younger director. Friedkin wanted The French Connection to be a film his uncle, who worked in a delicatessen in Chicago, could understand. Boiled down to its essence, this is a story about French crooks planning to sell heroin in New York and the cops trying to stop them. It’s full of chases: Popeye Doyle pursuing Fernando Rey on the subway or, most famously, Doyle driving at breakneck speed beneath the Elevated Railway as the train carrying a hitman whizzes by above him.