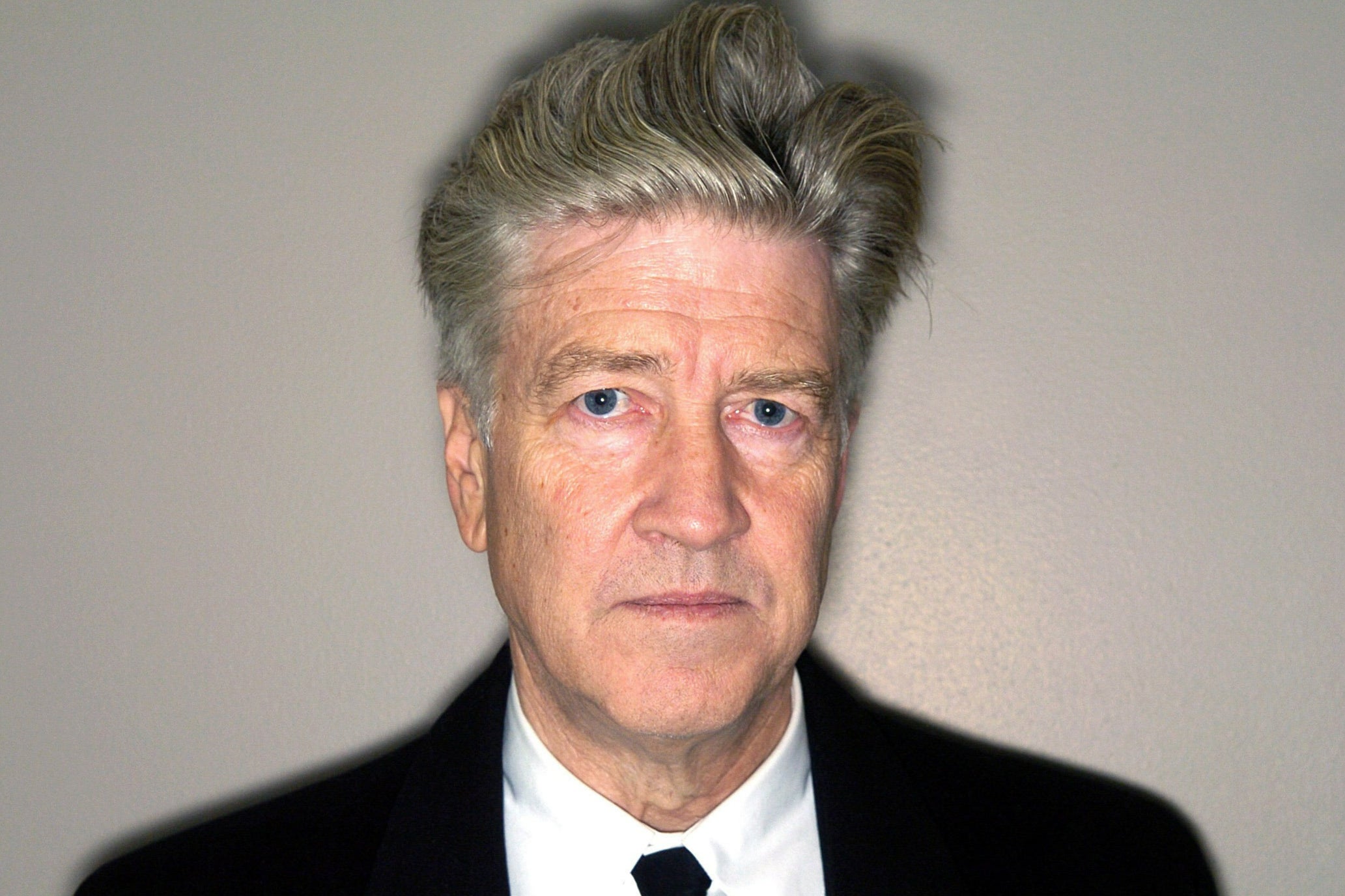

David Lynch, the visionary artist who made films that no one else could

Share:

The singular American filmmaker died this week at the age of 78, leaving behind a legacy like no other. Louis Chilton looks at the life and work of a man who redefined what cinema itself could achieve. Words feel inadequate when it comes to David Lynch. They feel particularly so now, in the wake of his death at the age of 78, months after the visionary American filmmaker announced he had been diagnosed with emphysema. How do you articulate such a loss – to cinema, to art, to the world? It feels like we cannot. But the truth is, Lynch has always seemed to operate in a realm beyond articulation – from his very first feature-length film, Eraserhead (1977), through to later masterpieces Blue Velvet (1986) and Mulholland Drive (2001), or Twin Peaks (1991-92; 2016), the show that revolutionised television two times over. Nouns, verbs and adjectives can only skirt the edge of Lynch’s strange, disorienting shadowplay, as if around the perimeter of a black hole. Veer too close, and everything gets lost in the great dark maw of it.

![[Jack Nance in ‘Eraserhead’]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/01/17/09/shutterstock_editorial_5878107g.jpg)

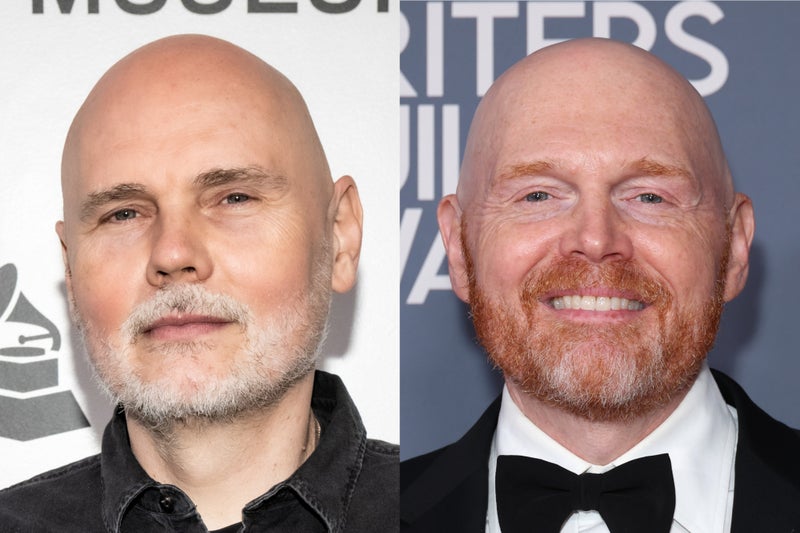

Of course, that has never stopped people from trying to find the right phraseology. It was only partway through his career that the term “Lynchian” was coined – a word many deploy, and far fewer are able to aptly define. It may be that Lynch’s work is just too hard to pin down: it brought together melodrama and noir, soul-shaking horror and head-scratching surrealism, increasingly casting aside conventional notions of narrative in favour of something foreign and elliptical. In his seminal article on Lynch, written around the production of Lost Highway (1997), the late David Foster Wallace wrote that the term “Lynchian” might be academically defined as “a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter”, but that it was “ultimately definable only ostensively – ie, we know it when we see it”.

![[Voyeur of the damned: Kyle MacLachlan in ‘Blue Velvet’]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/01/17/09/shutterstock_editorial_5882911j.jpg)