The UK music industry is reporting record revenues. The reality is much gloomier | Eamonn Forde

Share:

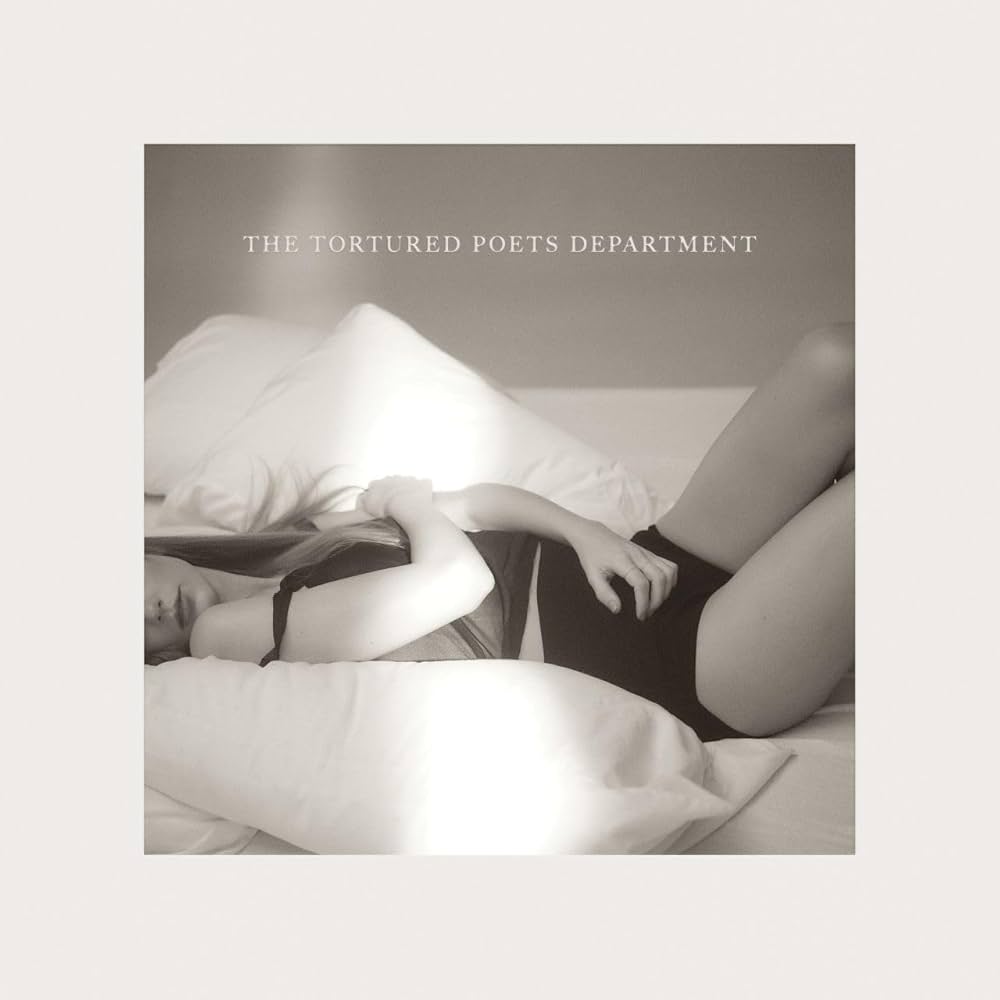

We’re apparently spending more on music than any time since the CD era – but the calculation methods are archaic, and don’t reflect the low incomes for many artists. News: UK music sales hit record high as Taylor Swift tops album sellers. If the record business has learned anything during those brutal years between 2000 and 2014 when the CD market wobbled and then went into such sharp decline that it halved, it is to seek out good news stories wherever you can.

![[Eamonn Forde]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/uploads/2022/04/26/Eamonn_Forde.png?width=180&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

The Entertainment Retailers Association (ERA), the UK trade body for music, video and games retailers, has just issued its numbers for recorded music revenues in 2024. The sell is that this marks “a 20-year high and an all-time record, exceeding the pinnacle of the CD era”. Let joy be unconfined. Bonuses all round.

![[The huge immersive screen at Outernet in London’s West End displays Spotify Wrapped, the top songs streamed by London in 2024.]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/0966cc98c468ba4455ca00143fbbee2bcf853b0a/0_0_5903_3935/master/5903.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

But trade numbers can only ever capture what the recorded music business is worth in toto. They tell us little of the depth and of the complexities of what has been happening here since the early 2000s. First of all, ERA states that subscriptions and purchases (LPs, CDs, downloads and cassettes) of recorded music reached £2,389m in 2024, overtaking the “previous high” of £2,221m in 2001. But that does not account for inflation – factored in, that £2,221m would be £4,080m in 2024. Pesky inflation makes for a less appealing headline.

ERA also reports that the “equivalent” of 201m albums were consumed last year in the UK compared to the 172m albums that were purchased in 2004 “at the tail-end of the CD boom”. That sounds impressive, but there is a complex numeric alchemy in how streams are converted into the “equivalent” of sales. For ERA, 1,000 subscription streams and 6,000 ad-supported streams (eg on the free version of Spotify) across any or all of the tracks on a particular album release are used to arrive at an aggregate and vaguely album-shaped number – but conflating streams and sales is like trying to amalgamate clouds and concrete.