Trump plots healthier America but deregulation likely to feature on menu

Trump plots healthier America but deregulation likely to feature on menu

Share:

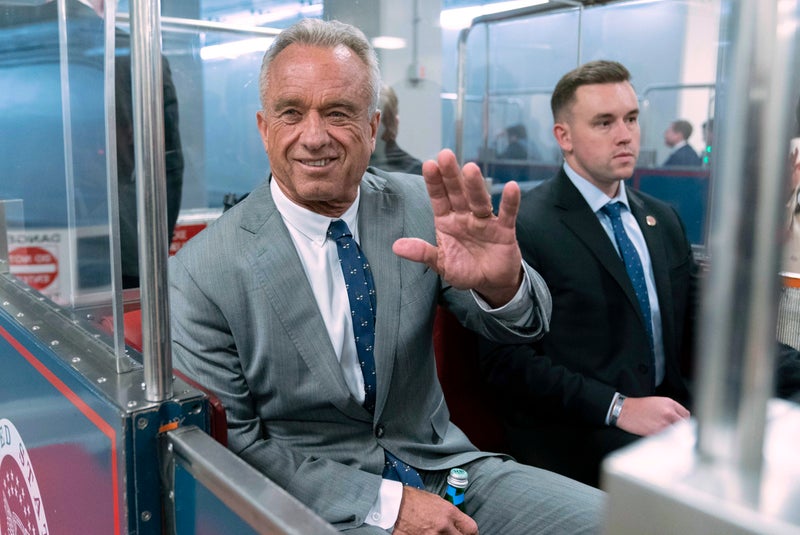

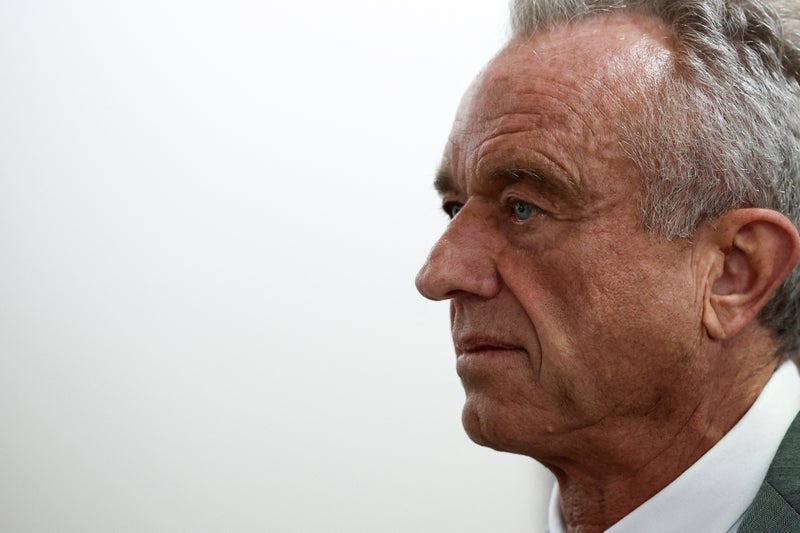

President’s cabinet picks suggest help for big companies and regulatory rollbacks will take precedence in food policy. When Robert F Kennedy Jr. suspended his campaign for the presidency in August 2024, throwing his support behind Donald Trump, he promised to continue fighting to “make America healthy again”. Kennedy’s criticism of ultra-processed foods and big food companies became a central feature of the Trump campaign. And after Trump was elected, he nominated Kennedy to be his secretary of health and human services.

![[Shoppers check out the Amazon Fresh store]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/433548239ed3e08ce11d362e33df8795ac47c31a/0_0_2400_1602/master/2400.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

Yet, just days before naming Kennedy, Trump nominated another senior official to his administration: Susie Wiles, a longtime lobbyist whose clients have included the same big food companies Kennedy has critiqued for their role in pushing ultra-processed foods into kitchens and grocery stores across the US. The two stood in stark contrast: a critic and a lobbyist for the food industry standing side-by-side the president-elect.

![[Farm workers use hoes to thin cantaloupe field]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/6c101da85b0e88d6c8af7e6c983826f53451bfa0/0_0_3000_1866/master/3000.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

Contradictions are one of the defining characteristics of Trump’s new inner circle – whether it’s the use of tariffs or certain immigrant visas – and food and agriculture policy are no exception. These conflicts, which range from mass deportations to food stamps, raise questions about what these policies under a second Trump term would look like. But the throughline, food policy researchers say, seems to be a willingness to present policies that deregulate industry while purporting to prioritize the health of everyday Americans (in addition to an abiding loyalty to Trump).

“I would not be surprised to see industry interests ultimately beating out any more recent rhetoric around commitments to health,” said Philip Kahn-Pauli, director of legislative affairs at the Center for Science in the Public Interest. “One of the bigger things that’s keeping me up at night is that we’ll continue to see trust in science come under attack, we’ll see misinformation and disinformation about nutrition and health proliferate and possibly even be platformed by government agencies, and that we’ll continue to see corporations benefiting at the expense of consumers.”.

Trump’s nominees – some of whom must still pass Senate confirmation hearings – have varied backgrounds on food and agricultural policy. Whether or not they’ll lead work on food or agricultural policy, their divergent opinions show the incongruities at play in the president’s incoming administration. On food assistance, there’s Office of Management and Budget nominee Russ Vought, who in his work authoring parts of Project 2025 has called for more than $400bn in cuts to food stamps. But there’s also education department pick Linda McMahon, who temporarily received food stamps in her 20s and has previously said she’d fight to protect them.

On farm workers, there’s Lori Chavez-DeRemer, nominated to be labor secretary, who has sponsored pro-union legislation and championed non-immigrant H-2A visas as a solution to the agricultural labor shortage. At the same time, there’s Tom Homan, the “border czar” who’s been tasked with overseeing mass deportations of undocumented immigrants, including thousands who labor in fields and factories picking and processing food.

And on climate, there’s Environmental Protection Agency head Lee Zeldin, who has a 14% rating from the League of Conservation Voters – and Florida-born officials such as Marco Rubio, who has been confirmed as secretary of state, and national security adviser Mike Waltz, who have been lobbied by local citrus growers after their state was devastated by hurricanes that have grown in magnitude as a result of the climate crisis.

There are officials who have called for greater regulations – such as Elise Stefanik, who’s called for restrictions around what kinds of companies can use words like “egg” to describe their products – and those who have called for fewer – such as Kristi Noem, who’s advocated for loosening rules around meat packaging. “I think it’s pretty clear across most, if not all, of the appointments that he is choosing people who will not say no,” said Karen Perry Stillerman, deputy director of the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Food and Environment program. That’s particularly clear in his choice for head of the department of agriculture: Brooke Rollins.

“We know so little about her in terms of what she thinks and knows about agriculture,” Stillerman said. Rollins previously served as head of the America First Policy Institute, a thinktank she founded in 2021 to further Trump’s policies, but which does not conduct agricultural research. “So I have no idea if she is someone who can tell her boss that he’s wrong and that something would be a bad idea or not.”.