Dr Saeed prescribed a teaspoon of shampoo for a cold during his thirty-year tenure as a bogus doctor. In an unassuming GP practice in Drewton Street, Bradford, Dr Muhammad Saeed treated his patients. A sociable and friendly man, he was gifted gold and silk shirts, and invited to the weddings of those he cared for. Arriving in the UK in the 1960s, he became a well-known face around Manningham, where a significant proportion of the city’s British Pakistani population first settled.

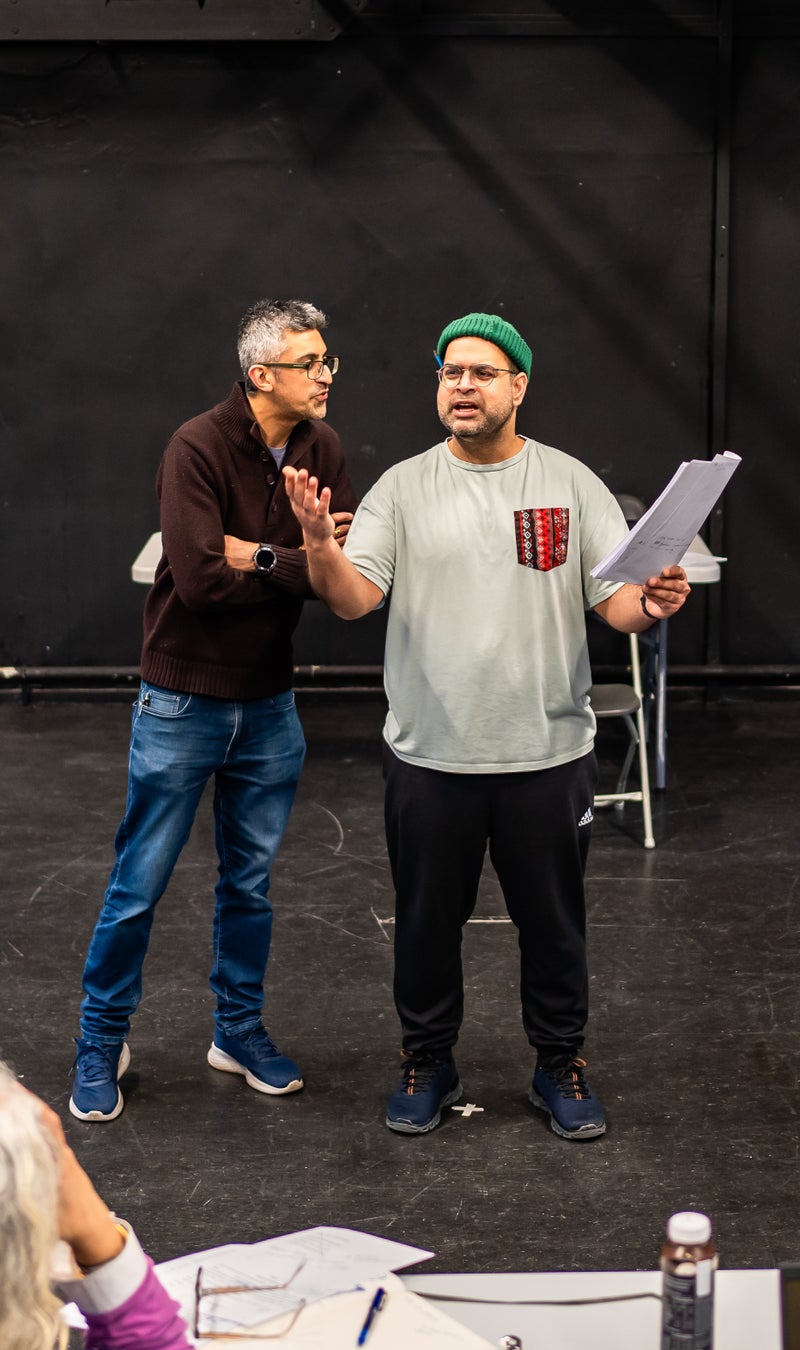

But despite his popularity, Dr Saeed held a secret that would eventually land him in prison – he wasn’t who he said he was. The clinician had managed to get a copy of a namesake doctor’s real qualification certificate dated 1949, which he used to register with the General Medical Council as a GP in 1961. It would be another 30 years and over £450,000 in earnings before he was caught. Set against the backdrop of a decline in the textile industry in Yorkshire in the 1960s, artistic director Dr Shabina Aslam discovered the story through a chance conversation with her late mother during the pandemic.

What followed was an all-consuming search through newspaper archives for the truth. During her research, former patients came forward with their testimonies. “I thought I'd write it as a short story because I couldn't believe what I found,” she told The Independent. “It was an international investigation and the police had gone all the way to Pakistan – along with the drug squad for some reason – to investigate the background of this fake doctor.”.

Infamous tales include Saeed prescribing the titular teaspoon of shampoo to drink for a patient suffering from a cold, and recommending a substance similar to the banned chemical creosote to cure a toothache. He was jailed for five years in 1992 after being convicted of four charges of obtaining pay by false pretences and property by deception. It was the pharmacist’s dispensing of his eccentric remedies that eventually raised the alarm.

But Dr Aslam is hoping for a more nuanced rendition of the story in her fictional retelling, which has since taken on the status of a fable in the local community. She hopes the play will tackle the ethical dilemmas at the heart of human nature. “The early immigrants that came to live in Manningham, would have spoken Punjabi, so that would have helped him,” she said. “He would have had largely Asian patients. People loved him. They absolutely adored him. People have a lot of affection for him. He was there for them. I don’t think he was a conman.”.

The play is told in the form of a fictionalised true-crime podcast and features dramatic recollections of key moments in his life, with audience asked to decide if Dr Saeed, known as Dr Muhammad Saad in the play, is innocent or guilty. “The play shows him in different ways including arrogant and falling apart,” says Dr Aslam. “The audience is offered different views of one character. The play looks at the doctor as a fallible human being.

“I want the audience to ask themselves: Was what he did harmful? He didn’t have the right papers, but was what he did morally wrong?”. She adds: “It's inspired by his story in order to get people to really think about human law versus jurisprudence versus Sharia law and Asian culture.”. Saeed died in 2003. Dr Aslam says her mission is to uncover hidden histories within the South Asian community at Theatre in the Mill, which is one of the only places in the UK to deliver an offering of 70 per cent Global Majority stories in their schedule.