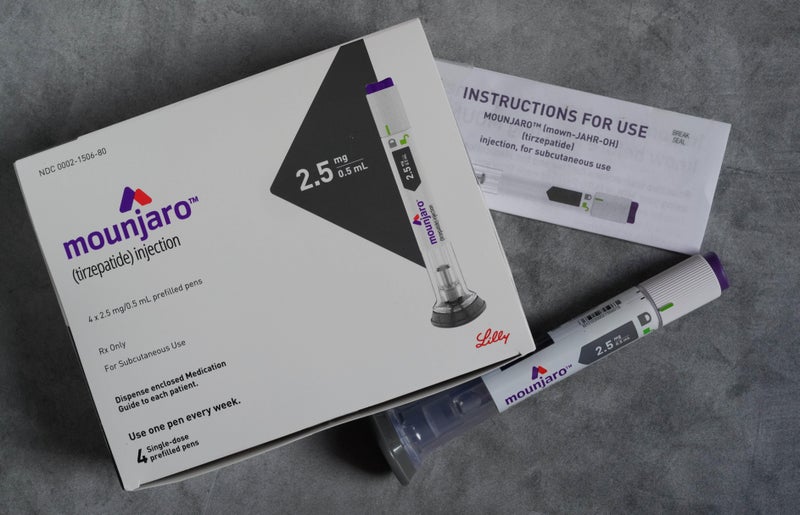

A groundbreaking clinical trial has revealed that weight-loss injections marketed as Ozempic and Wegovy may significantly reduce alcohol cravings and heavy drinking. The study, the first of its kind, found that a weekly dose of semaglutide decreased the amount of alcohol consumed daily by approximately 40%, alongside a dramatic reduction in the desire for alcohol. These findings corroborate reports from both patients and doctors who have observed a sudden decrease in alcohol cravings among those taking semaglutide.

![[A PA graphic showing the number of alcohol-specific deaths in the UK]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/02/05/11/08ae7fb225373ac13dc396861f7bff4cY29udGVudHNlYXJjaGFwaSwxNzM4ODQxNzE5-2.78911429.jpg)

The research adds to a growing body of evidence suggesting that the drug’s benefits extend beyond weight management and diabetes control. Previous studies indicate semaglutide may also reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke in overweight individuals and improve heart failure symptoms. The new study comes after UK figures published last week showed deaths from alcohol have reached a record high.

![[The injectable drug Ozempic is shown, July 1, 2023, in Houston.]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/01/17/17/AP25017529348951.jpg)

Some 10,473 deaths were registered in the UK in 2023 which were the direct consequence of alcohol, such as alcoholic liver disease. This was 4% higher than they year before. In the latest research, published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry, 48 people with problem drinking were recruited who had not been actively seeking treatment. They all had alcohol use disorder, which can include the inability to stop or control drinking despite negative consequences.

For the study, people were taken to a comfortable lab setting one week before injections and asked to drink their preferred alcoholic drinks over two hours, with instructions to delay drinking if they wished. They were then randomly assigned to receive weekly, low-dose injections of semaglutide or a placebo for nine weeks, during which time their weekly drinking patterns were also measured. The semaglutide dose was 0.25 mg per week for four weeks, 0.5 mg per week for four weeks, and 1.0 mg for one week, all given during clinic visits.

Afterwards, everyone returned to the drinking lab to repeat the process and see what had changed. Researchers calculated how much alcohol people had drunk and their breath alcohol concentration. The findings showed that semaglutide injections reduced the amount of alcohol people drank in the lab setting, “with evidence of medium to large effect sizes for grams of alcohol consumed”. The semaglutide group also saw a 41% reduction in the number of drinks they consumed on each of their drinking days.

Furthermore, weekly alcohol cravings dropped by around 40%, while there were also bigger reductions in heavy drinking over time compared to the placebo group. Nearly 40% of people in the semaglutide group reported no heavy drinking days in the last month of treatment, compared to 20% in the placebo group. Among a small group who also smoked cigarettes, those treated with semaglutide smoked less than those in the placebo group.

The researchers said a key finding was that semaglutide’s effects were bigger than is often seen with existing drugs to curb alcoholism, even though semaglutide was only administered at the lowest clinical doses. Senior author Klara Klein, from the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, said: “These data suggest the potential of semaglutide and similar drugs to fill an unmet need for the treatment of alcohol use disorder.

“Larger and longer studies in broader populations are needed to fully understand the safety and efficacy in people with alcohol use disorder, but these initial findings are promising.”. Professor Sir Ian Gilmore, chairman of the Alcohol Health Alliance UK, said: “We welcome any new research developments to help people with alcohol use disorders. “While the evidence on the efficacy of these new drugs remains limited, we do have decades of robust research showing how to help people with alcohol problems and prevent alcohol harm more broadly by tackling the affordability, availability and marketing of alcohol.