Brother of the Dalai Lama and political envoy who led talks on the exiled leader’s return to Tibet with the Chinese government. The life of Gyalo Thondup, who has died aged 97, was transformed after one of his younger brothers, Lhamo Thondup, was identified by senior Tibetan monks as the reincarnation of the great 13th Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader who in 1912 had declared Tibet’s independence. In 1940, the boy was installed as the 14th Dalai Lama.

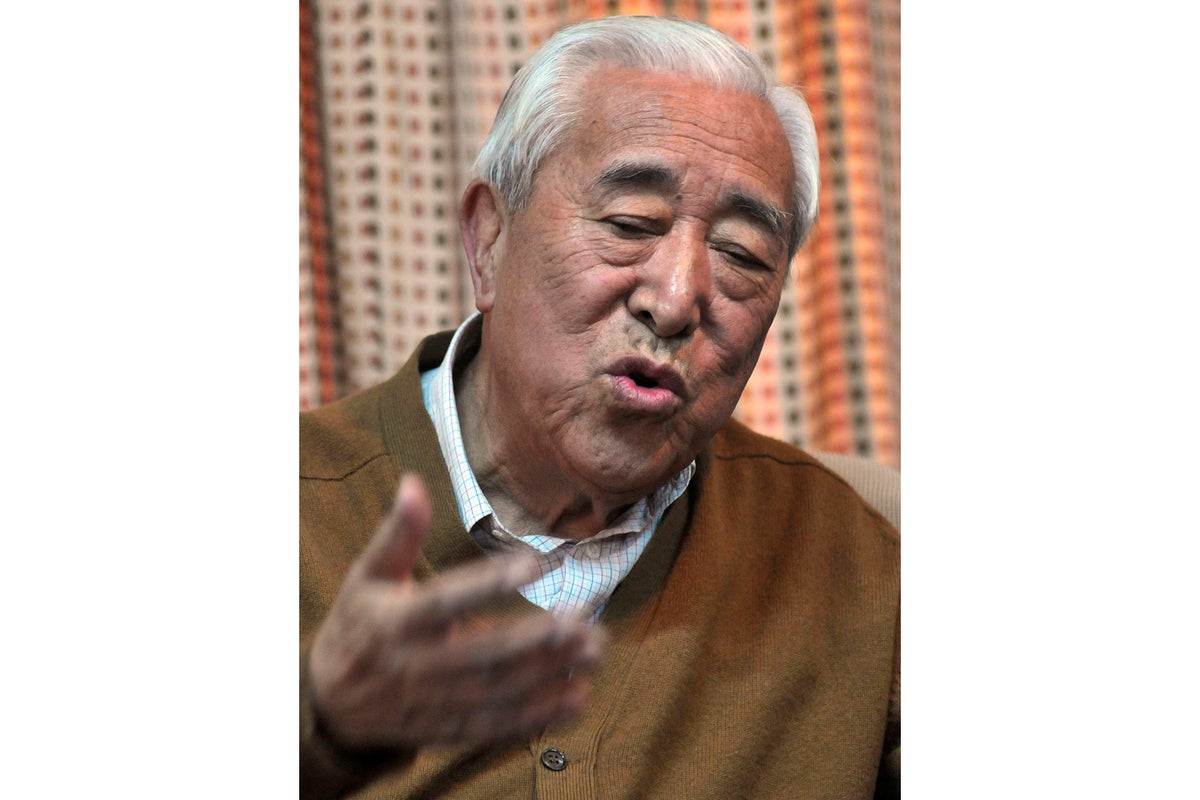

![[Xi Zhongxun, China's vice-premier and father of president Xi Jinping, with Gyalo Thondup in Beijing, 1987.]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/9abdd56272c8f693804e7b360a538e9bafc547f4/0_239_2500_1500/master/2500.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

At once, they were catapulted to being the leading family in the country, swapping their farmhouse for a mansion in the city of Lhasa, where Gyalo attended a private school for the children of aristocrats. In 1942, aged 14, he was sent to Nanjing, China.

This led to his meeting the president of what was still the Republic of China, Chiang Kai-shek, who regarded the young Tibetan as the ideal person to liaise between himself and the Dalai Lama as soon as the latter came of age. It was a policy of the nationalists – no less than of the communists – that Tibet should be reunited with the motherland. In his 2015 autobiography, The Noodle Maker of Kalimpong, Thondup recounted how he had been a frequent houseguest of the president and his wife, who came to treat him “as a son”.

Not long after the communists came to power in 1949, they moved troops into Tibet. Thondup – who had by now separated from a Tibetan wife and married the daughter of a high-ranking officer in the nationalist navy – soon fled to Kalimpong, West Bengal, where there was already a large community of Tibetan exiles. During the winter of 1949-50, the Dalai Lama left Lhasa for southern Tibet, with a view to possibly seeking asylum in India.

It was at this time that Thondup first came into contact with the CIA. Concerned at the loss of China to the communists, the US state department was keen to build relationships with the Dalai Lama’s government. Thondup, who had emerged as de facto leader of the Tibetan émigrés, was approached by the CIA. Although never anti-Chinese, Thondup was, as might be expected, staunchly anti-communist. As the situation in Tibet deteriorated, the US decided to arm a resistance movement.

Thondup was charged with identifying six candidates who were exfiltrated to a CIA base on Okinawa, Japan, for training in intelligence gathering and sabotage. To their surprise, their translator was the eldest brother of Thondup and the Dalai Lama, who had acquired the name of Taktser Rinpoche and a position as abbot of an important monastery through another reincarnation. Having fled the Chinese and renounced his religious vocation, he too had become a CIA asset.

The agents that Thondup recruited impressed the Americans sufficiently for them to mount a full-scale operation in Tibet. Training was switched from Okinawa to a secret base at Camp Hale, Colorado, where 250 agents – most of them ex-monks and all recruited by Thondup – received training.

When the Dalai Lama fled Lhasa for India in March 1959, he established contact with some of them. As a result, though the fact was kept secret for decades, the US president, Dwight D Eisenhower, and, through him, the Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, were kept aware of the Dalai Lama’s movements almost from the start.

US support for the Tibetan resistance continued throughout the early 60s, but tailed off as it became clear that the Chinese would not easily be dislodged. The agents did some sabotage, including blowing up an armoury and damaging some convoys, but the main effect was to harden Chinese resolve. For his part, Thondup spent the next decade or so pursuing various business interests, including a noodle factory.

He also had a direct role in the Tibetan government in exile. In 1959, 1961 and 1965 he promoted resolutions relating to Tibet by the general assembly of the United Nations in the course of handling its foreign affairs, and in the early 90s he became the chairman of the Kashag (cabinet). In between he established a base in Hong Kong, in addition to a residence in Kalimpong.

His apparent success caused considerable envy and questioning within the exile community. He was a key figure in the sale in the early 60s of about $2m worth of gold that had been sent from Tibet in 1950 and had been held in safekeeping for the Dalai Lama by the maharajah of Sikkim. Investments were made in various Indian enterprises, none of them successful, with the result that an inventory taken four years later showed their value had fallen to just a third.

When news of this reached the Tibetan community in exile, several people involved in the debacle, chief among them Thondup, came under suspicion. But despite the rumblings of discontent, he retained the confidence of the Dalai Lama and became his chief envoy, first to the Indian government and then to the Chinese government.

In 1979, after the death of Mao Zedong and in the wake of Deng Xiaoping’s opening of China, Thondup visited the Chinese premier for a discussion about a possible return of the Dalai Lama to Tibet. Partly as a result of this meeting, several fact-finding missions from the Tibetan government in exile visited Tibet with a view to the Dalai Lama himself doing so in 1985.