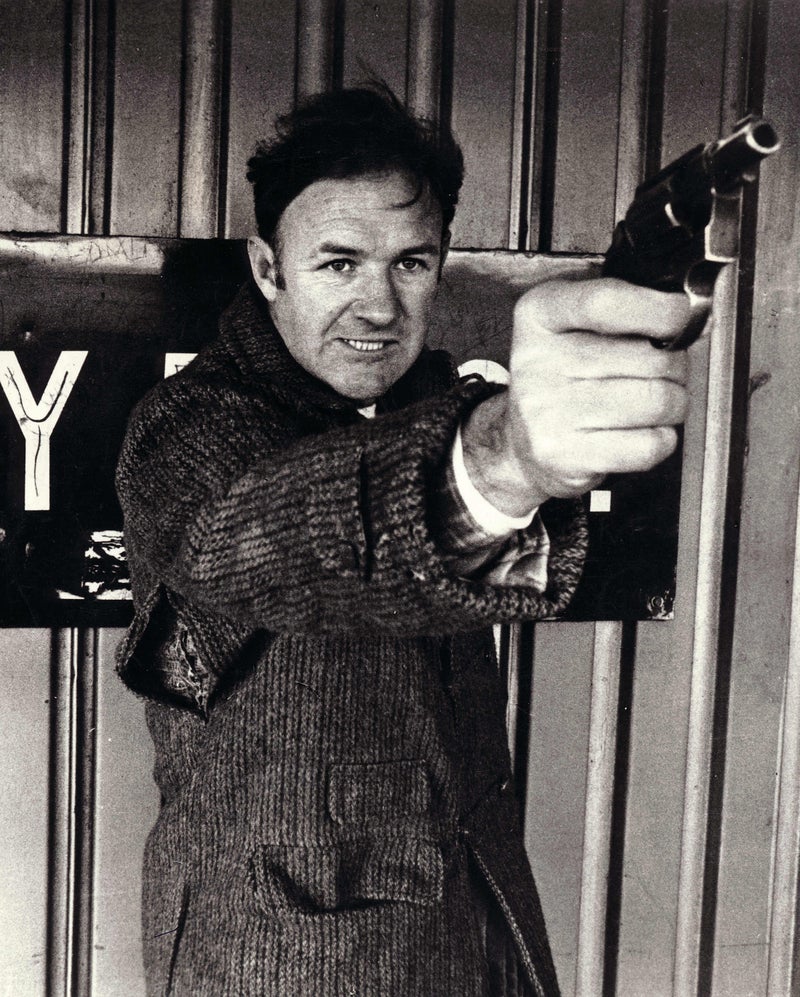

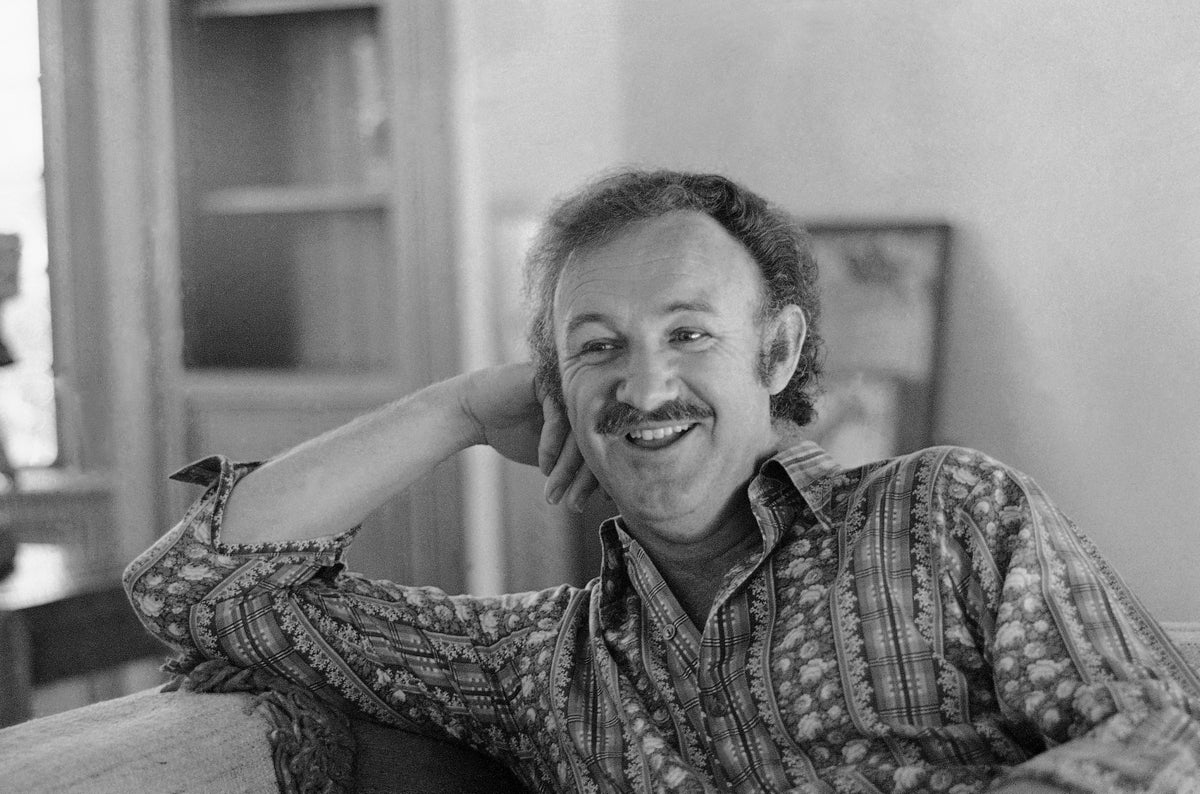

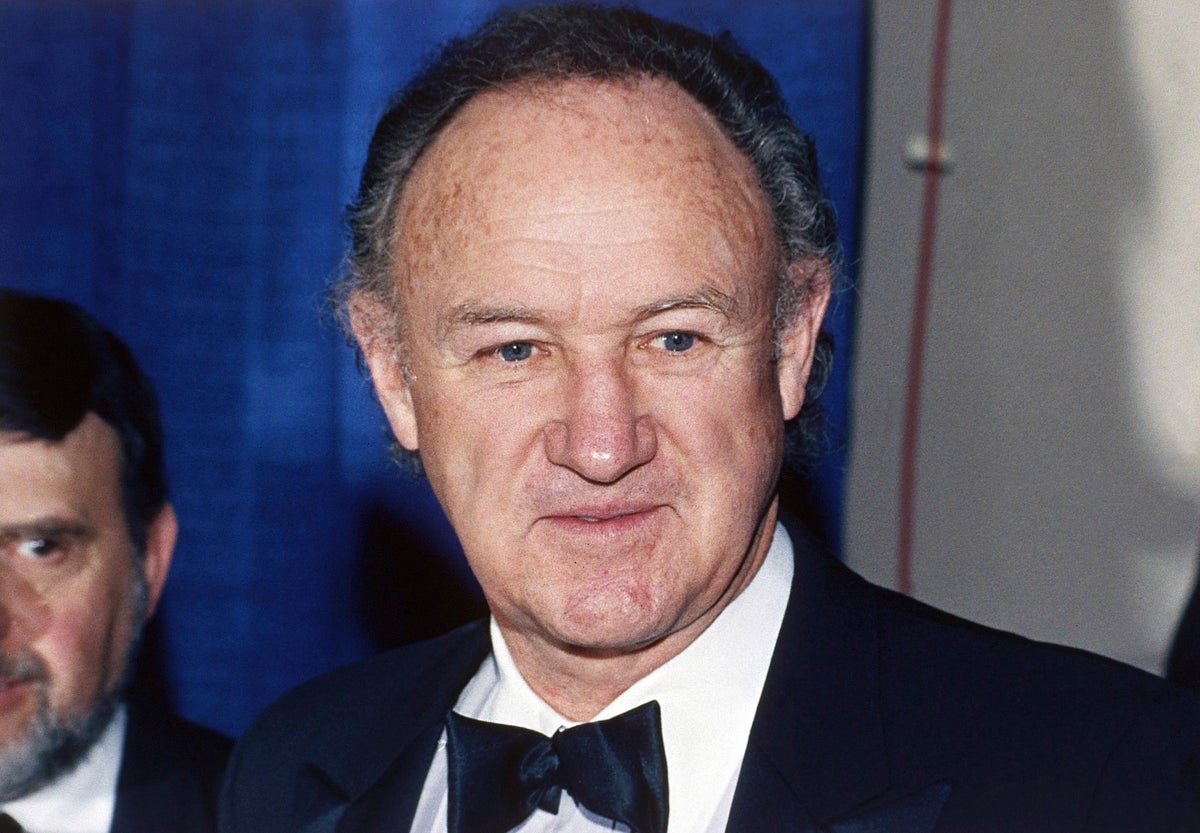

Hackman, who was found dead this week at the age of 95, was one of the Hollywood’s greatest actors – and one of its least conventional leading men. It’s hard to imagine anyone like him reaching these levels of success now, writes Louis Chilton. There really was no one like Gene Hackman. The man some consider to be the finest actor of his generation – if not the entire 20th century – was found dead this week at the age of 95, under upsetting and currently uncertain circumstances. Hackman was a fiercely naturalistic actor, often described as an “everyman”: this was the descriptor that marked the headline of his New York Times obituary, for instance. He was an unconventional leading man, but a leading man nonetheless. Many of his best performances (the shifty, obsessive Harry Caul in The Conversation, or The French Connection’s flinty and problematic “Popeye” Doyle) dominated entire films: they are the sort of roles that actors dream of.

What, though, would modern-day Hollywood have made of an actor like Hackman, were he coming of age today? Hackman had a truly great face – narrow, expressive eyes, a remarkable grin and scowl, and a majestic forehead – but not the sort of face that you usually find on movie stars. He got into movies relatively late, breaking through in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) at the age of 35. Most of his best roles came in middle age.

When we think of recent stars who have found stardom at the age Hackman did, they are a vastly different proposition. Someone like Hit Man’s Glen Powell, for instance, has recently been characterised as a late bloomer, rising to prominence in his mid-thirties. Powell, though, is a conventional Hollywood hunk through and through, charming and photogenic (and with a thick head of hair). Adam Driver is often cited as an example of an unusual-looking actor who has managed to become a generational leading man, fronting meaty, interesting films from Michael Mann, Martin Scorsese and Noah Baumbach among others. But there’s no comparing him with Hackman; ever since his early days as a regular on Girls, Driver has always been something of a left-field sex symbol. He is not an “everyman” at all, nor does he try to be.

It’s not that there is a dearth of leading roles for actors in their forties, fifties and beyond, but that these roles are reserved for actors who were renowned for their good looks. Colin Farrell, Tom Cruise, Keanu Reeves, Paul Rudd, Leonardo DiCaprio, Denzel Washington: these are the sort of men for whom stardom has endured. Some of the best actors around with less conventional faces – Forest Whitaker, for example, or Paul Giamatti – have endured periods of real creative inertia, long periods where Hollywood failed to produce projects worthy of their talents. The Holdovers, last year’s droll and moving drama set in a boarding school, reminded everyone just how good an actor Giamatti is, but also begged the question: where the hell had he been for the last decade?.

Often, talented actors who might not look like Cary Grant get shepherded into the field of so-called character acting. The defining traits of a character actor, in common usage, are that they are good at what they do, and that they are never the leading man. (Think of Robert Duvall, a contemporary of Hackman with a similar “everyman” look about him; the Godfather star became renowned as Hollywood’s “Number one number two”.) Hackman was built to be a character actor, and certainly turned in his share of stellar supporting performances, in projects such as Unforgiven and Bonnie and Clyde. But he was never restricted to this, and filmmakers didn’t hesitate to put him in the spotlight.

It may be that Hackman was lucky: the New Hollywood moment may have been the only time the film industry was fit to accommodate a talent like his. Under the old studio system, leading men were often very of-a-piece, aesthetically – and in any case the performing style of the time may well have jarred with Hackman’s brand of rough-edged verisimilitude. It’s hard, too, to imagine what parts Hackman would have played had he been a couple of decades younger: the roles that seem to fit his profile are few and far between.

Watch a run of Hackman’s best 1970s and 1980s films, and it’s glaring just what we’re missing these days, just how much has been lost. The era of the “everyman star” is long gone. It’s more than just a shame for talented actors in the Hackman mould; anyone interested in seeing life reflected on screen loses out. It’s a narrowing of storytelling itself, a slow shuttering of the horizon. We can hope that the emergence of a new actor with Hackman’s stratospheric talent would be enough to convince studios to change. But we can only hope.