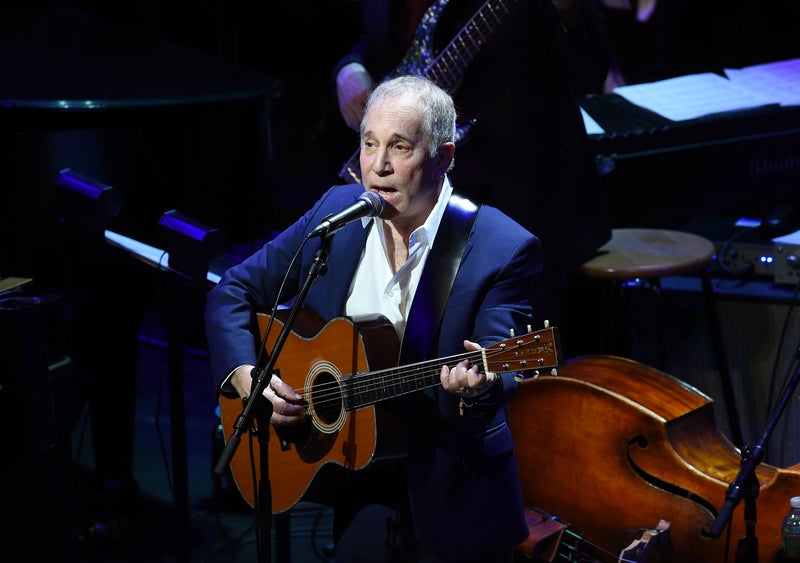

As the ‘Baywatch’ star draws raves for her first dramatic acting role in ‘The Last Showgirl’, Adam White looks back on another pop culture pin-up whose attempt to change her image in the public eye via gritty character parts had only a short-term effect. Pamela Anderson is the Marilyn Monroe of our time,” the filmmaker Gia Coppola claimed last year, after casting Anderson in her first dramatic movie role. Anderson’s performance, in Coppola’s featherlight paean to old Hollywood glamour The Last Showgirl, has drawn the actor raves (and a recent Golden Globe nomination). She’s good in the film, as a fading burlesque dancer haunting the Las Vegas strip, giving a performance that, while warm and endearingly bruised, is also carried by its metatext: Shelly, in The Last Showgirl, is a beautiful symbol of an industry that’s moved on without her, a woman who’s never quite been taken as seriously as she should have been (or wanted to be).

![[A dramatic force: Pamela Anderson in ‘The Last Showgirl’]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2025/02/07/15/00/TLS-image-1.jpeg)

It’s not hard to see the real-life parallels. Or why Coppola drew links between Monroe and Anderson. Like Monroe, Coppola added, Anderson was for years a woman “really craving to express herself as an actress creatively ... [who] was really hungry to show her talents”. But Monroe isn’t the best of analogues. If anything, it’s the late Charlie’s Angels star Farrah Fawcett whose career offers more overt parallels to where Anderson has come from – and where she might try to go next.

In the wake of the skimpy, silly action series that catapulted her to fame, Fawcett was for years typecast as doltish blondes (whatever you do, do not watch Somebody Killed Her Husband, her ill-fated 1978 team-up with Jeff Bridges). Like Anderson, she was also immortalised in pop-culture history via a red swimsuit (Anderson in Baywatch, Fawcett on the best-selling poster of all time). And as rough around the edges as The Last Showgirl is, it does feature a performance from Anderson that hints at a dramatic force in the making – much like Fawcett’s run of compelling dramatic roles in the Eighties and into the Nineties, from the vigilante thriller Extremities to the domestic violence drama The Burning Bed.

Fawcett died from cancer in 2009 at the age of 62, her death famously eclipsed within hours of its announcement by the news that Michael Jackson, too, had died. In obituaries, much was made of her saddening final years in a seemingly toxic on-again, off-again relationship with the troubled actor Ryan O’Neal, as well as her erratic public behaviour. Her last film role was as a racist trophy wife in the Queen Latifah comedy The Cookout (2004), in which she tossed around the n-word as a punchline. Her last on-camera roles were in the various reality shows and documentaries she participated in during the Noughties, which – in accordance with the schlock-TV demands of the era – foregrounded uneasy voyeurism rather than empathy. She was often memorialised euphemistically, as a “sex symbol” or “tabloid star”.

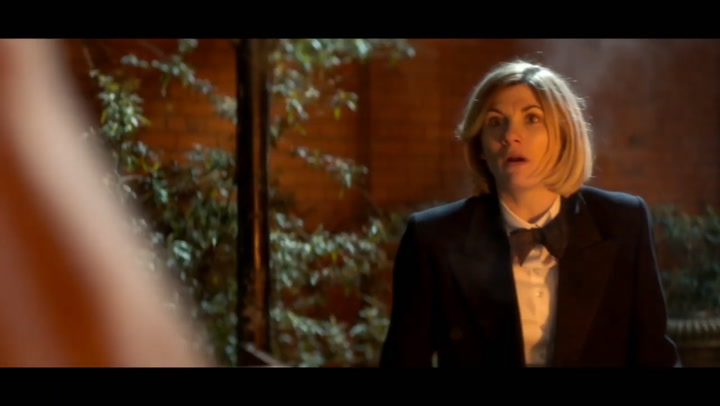

Eager to prove her skillset, Fawcett ventured to New York and acted on stage, replacing Susan Sarandon in a provocative play about a rape survivor who turns the tables on her attacker. Extremities was turned into a film in 1986, also starring Fawcett. She is quite remarkable in it, brittle and tortured, with a sliver of slight madness to her line readings as she grows increasingly frayed. It was a performance that built on the soft-voiced fragility she brought to the 1984 made-for-television film The Burning Bed, in which she played a wife and mother abused by her husband. Fawcett received a Golden Globe nomination, and in 2016 the journalist Matt Zoller Seitz named her performance “one of the finest in the history of TV movies”.

“My image certainly hurt me, and yet that is also what made me successful and eventually able to do more challenging roles,” Fawcett said in 1986, reflecting on her career up to that point. “That old image was so strong that I don’t think it will die easily. I’ll have to do a lot of good work, but that’s all right ... I would like to reach my potential.”. Opportunities, though, were few and far between. Fawcett would take on only a handful of big-screen roles in the wake of Extremities, among them a (better) team-up with Jeff Bridges in the handsome 1989 comedy See You in the Morning, and the part of Robert Duvall’s wife in his Oscar-nominated rural drama The Apostle in 1997. She is wonderfully subtle in the latter, flinching lightly from the volatility of Duvall’s character, a pentecostal preacher whom she intends to divorce. Outside of a cameo in Robert Altman’s misfiring 2000 comedy Dr T & the Women, in which her character suffers a nervous breakdown and climbs nude into a fountain, it was the last role that truly asked something of her.