In Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, people have watched the ice fields turn to exposed rock and experts predict these vital water sources could be lost in 30 years. At an altitude of 4,200 metres in the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, Colombia, Edilsa Ibañéz Ibañéz lowers a cupped hand into the water of a glacial stream. A local guide and mountaineer, she has grown up drinking water that runs down from the snowy peaks above. As she stands up, however, the landscape that greets her is markedly different from that of her childhood.

![[The face of a woman wearing a hat in the sunshine]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/7a53e480dd97a68b3da77cf9591af7e70736bf75/0_0_5000_4000/master/5000.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

“We used to think the ice would be eternal,” says Ibañéz, 45. “Now it is not so eternal. Our glaciers are dying.”. The Sierra Nevada del Cocuy is one of six remaining glaciers in Colombia. Although it has lost more than 90% of its ice since the second half of the 19th century, Ibañéz says it contains about 36% of the country’s total glacial coverage.

![[A stone marker near the edge of some ice with a sign saying ‘Limite glaciar 2018’ ]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/d4c8da39b60e596433bdf1cc3eb9790433a5be60/0_0_4632_3706/master/4632.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

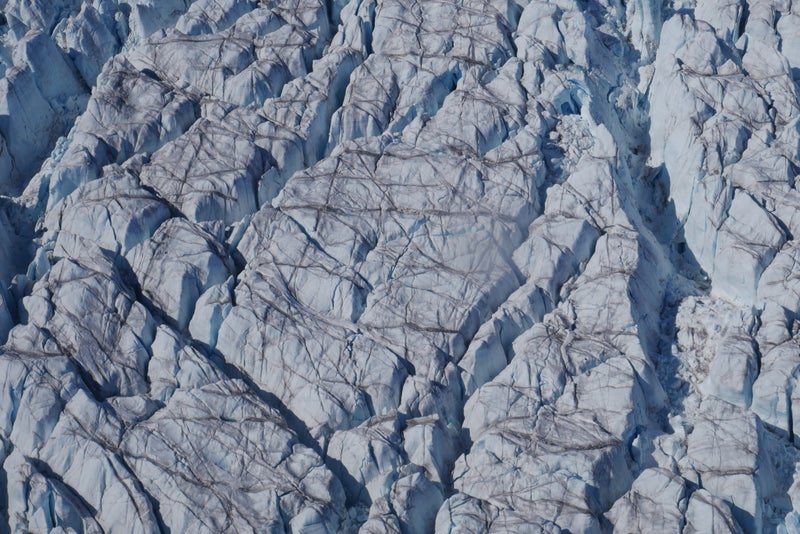

Swathes of dry rock are exposed in areas once carpeted in snow in the high Sierra Nevada peaks. On the trail leading to the Cóncavo peak, stone markers have been placed like gravestones to indicate the position of the snow line in years past. The farthest marker, dating from the end of the 19th century, is several kilometres from the nearest ice.

![[A hollowed out section of a glacier with rock showing between and fragments of ice lying around]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/86fc4002ac615256b6891518da884837b74f3c08/0_0_5000_4000/master/5000.jpg?width=465&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

The peak itself presents a similarly grim picture. Fingers of greying ice slide towards the rocky mass below, where frozen boulders soften and thaw in the harsh sun. Deep within the glacier, the shifting ice emits loud cracks that rattle through the thin air above.

![[A woman’s cupped hand raises water from a stream]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/12e67e9b6a0a349cea6a302a8348e2c98a6a6e1d/0_0_5000_4000/master/5000.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

Although the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy is home to the largest glacial mass in the country, it is far from alone in its fate. Rising global temperatures and increasingly unpredictable weather patterns are devastating all six of Colombia’s remaining glaciated areas.

![[A man standing on a mountain wearing a poncho and cap]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/ecc22b8c17eba39e41260b798b010b4caf06296a/0_0_5000_4000/master/5000.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

In 2024, neighbouring Venezuela became the first country in modern history to lose all its glaciers, and some predict that Colombia could go the same way in as little as 30 years. “Even if we were to very aggressively over the next 10 to 20 years reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it wouldn’t be enough,” says Mathias Vuille, a professor of atmospheric and environmental sciences at the University at Albany, who has been studying the climate crisis in the Andes for more than 30 years. “They aren’t accumulating any fresh snow and ice any more – they are doomed.”.

![[Cactus-like plants against a blue sky in the Sierra Nevada El Cocuy]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/8f7d02afc325fb5b9129456d025756e3bcb68120/0_0_4862_3890/master/4862.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

Colombia’s lowest-lying glacier, Santa Isabel in Los Nevados national park, far west of the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, will probably be the first to disappear. According to data from the Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (Ideam), it will probably be gone within five years.

![[An small path winds across a hillside of burned plants]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/e1d4c50b3809b1b9a4024d35d3d3217d8b53bfcc/0_0_5000_4000/master/5000.jpg?width=465&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

Matteo Giraldo, 32, from the nearby city of Pereira, has been walking in the mountains around Santa Isabel for the past 16 years. “I’ve cried for the situation with the glacier,” he says. “To see it before and after has been something I’ve felt in my heart.”.

![[Head and shoulders portrait of Doris Ibañéz Cristancho wearing a black beret]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/d8fb40d75b2e97c597a9e50db7b1e9cdd3ed0187/0_0_5000_4000/master/5000.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

Along with others who have frequented the glacier in recent decades, Giraldo has seen firsthand the changes that caused one section, Conejeras, to disappear entirely between December 2023 and February 2024. The loss of Colombia’s glaciers poses a ticking timebomb for those living in the country’s high-altitude regions.

Vuille says: “Glaciers are constantly melting in the tropics – that means they constantly release water. That’s why they are essential, like a reservoir. It is your only water source if you live very close to the glacier.”. The ability of glaciers to retain and release vast quantities of water makes them a vital source for communities living across the Andes. The Sierra Nevada del Cocuy alone contains the equivalent of about 256,000 Olympic swimming pools of water.

Unlike their counterparts in higher-latitude regions, such as Europe and North America, Colombia’s tropical glaciers are relatively constant in temperature. This results in a shorter period of ice accumulation and a longer, year-round period of water release. People living in Colombia’s mountains rely heavily on the swiftly diminishing glaciers for their main water supply.

Ibañéz and her relatives, who live at the foot of the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, consider themselves part of this group. “Very soon, we will be the first to run out of water,” she says. “Most people here aren’t aware of this.”. Hernando Ibañéz Ibañéz, Edilsa’s brother and a community leader, fears for the future of his community. “Right now, I have 250 families dependent on one aqueduct,” he says. “According to what we observe daily, in 10 years we will no longer have this aqueduct. This is a concern for future generations.”.

As Colombia’s glaciers hurtle towards extinction, they serve as an alarm bell signalling a much broader pattern of environmental degradation already straining the entire country’s water supply. After historic droughts across Latin America, the country’s capital of Bogotá is still zonally rationing water – residents were asked to “shower together” to preserve diminishing water supplies in 2024.