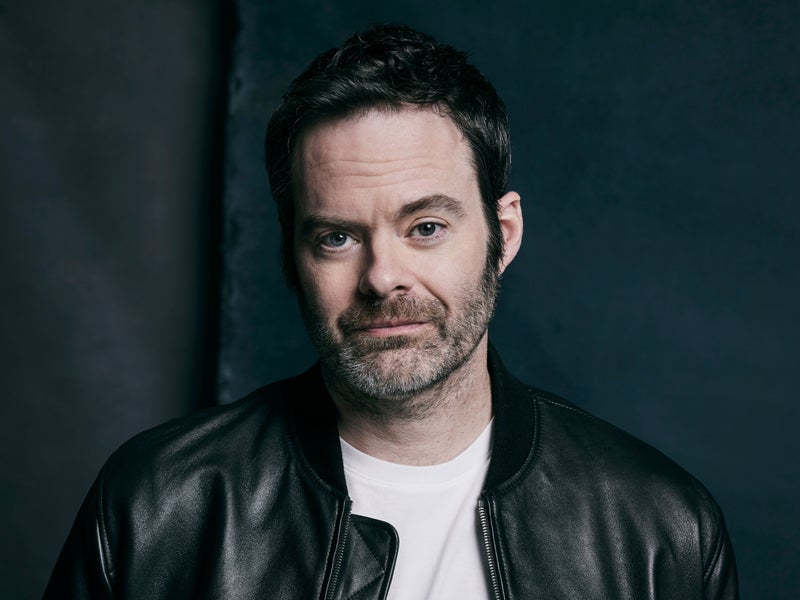

‘I don’t like the way I sound. I don’t like the way I look. It’s just embarrassing’: Bill Hader on Barry, anxiety and body image

‘I don’t like the way I sound. I don’t like the way I look. It’s just embarrassing’: Bill Hader on Barry, anxiety and body image

Share:

As the final season of his hitman comedy-drama ‘Barry’ airs, ‘Saturday Night Live’ hero Bill Hader talks to Patrick Smith about stage fright, Star Wars, and the roles he’d no longer play. Bill Hader appears on my screen from Los Angeles, unshaven, a little groggy and in an uncluttered white room. Faced with this pixelated version of him, I’m instantly reminded of his role in the 2008 Judd Apatow-produced romcom Forgetting Sarah Marshall, for which he appeared almost exclusively on video call, in the days before Zoom was a thing. “It was such a novelty back then,” he says, that furrowed brow unmistakeable. “It was like, ‘Whoa, this is new.’”.

![[Behind bars: Bill Hader as Barry Berkman in ‘Barry’]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2023/04/17/10/newFile-3.jpg)

Saturday Night Live’s erstwhile Man of a Thousand Faces is here on my laptop to talk about his greatest creation, Barry Berkman, a marine turned assassin turned aspiring actor in the HBO comedy-drama Barry, which Hader writes and directs as well as playing the title character. The show has won multiple Emmys; critical adulation; obsessive fans. What began as an apparent riff on the hitman-with-a-heart-of-gold trope has evolved over four seasons into something richer: a thrilling synthesis of showbiz satire and character study, with pitch-black humour and nail-biting suspense. As we get to know Barry, the notion of him as simply a stoic, ruthlessly efficient killer slowly dissipates.

![[Hader as Stefon with Ben Affleck in ‘Saturday Night Live’]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2023/04/21/14/newFile-2.jpg)

“I like the John Wick movies,” says Hader. “But this wasn’t John Wick. This wasn’t ‘assassin’ in a genre sense.” The show was more about “the real idea of a hitman”, he explains. “The loneliness of it, and how murdering people affects his psyche.” Hader points to Tony Gilroy’s 2007 legal thriller Michael Clayton as an example of how to get hitmen right. “I liked that scene when Tom Wilkinson gets killed,” he says. (The hitmen make the attorney’s murder appear to be suicide.) “I always thought that was a good, realistic fixer hit scene. It was so shocking.”.

![[Hader (left) as a cop in the ribald 2007 comedy ‘Superbad’]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2023/04/21/17/shutterstock_editorial_5884805k.jpg)

Hader’s face is an orchestra of expressions, all quivering eyebrows, wolfish smiles, and grimaces played for laughs. He is dry and laconic, with a midwestern accent that flits between adenoidal and baritone. He is also, by his own admission, a bundle of anxiety, which seems to manifest itself in moments of quiet self-effacement or hyper-critical introspection. Maybe it’s no surprise, then, that Barry so successfully probes the darkest corners of the human condition while retaining a gloriously offbeat sense of humour.

![[Bill Hader: ‘I find if there’s a drama that doesn’t have some humour in it, it usually doesn’t work’]](https://static.independent.co.uk/2023/04/21/14/newFile-3.jpg)

Not that the end of the last series was particularly funny, as Barry’s sinister past finally caught up with him. “When season three aired, people were like, ‘Wow, it’s not really a comedy any more,’” says Hader. “And I was like, ‘What do you mean?’ And then you go back and watch that last episode of season three, and I’m like, ‘Oh yeah, really funny.’” He’s being sarcastic, of course. As with Breaking Bad, a drama to which Hader says his show is indebted, Barry is very comfortable plumbing the depths of humanity. Abusive relationships, PTSD, mass murder: the series tackles it all, with an unnerving smile creeping out from the corner of its mouth. “I find if there’s a drama that doesn’t have some humour in it, or if there’s a comedy that doesn’t have some sort of real representation of human emotion or something,” he says, “it usually doesn’t work.”.

An exception, he adds, is The Naked Gun, which “doesn’t need any pathos – it’s just really funny”. He showed the 1988 film, which stars Leslie Nielsen as a bungling detective, to his three daughters during the pandemic. “I was laughing so hard,” says Hader, for whom watching comedy has always been a family affair. Indeed, growing up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the son of a dance teacher and the owner of an air cargo company, Hader became obsessed with the surrealist farce of Monty Python. “My dad was a massive fan,” he says. “A ton of stuff from Monty Python’s Flying Circus didn’t make sense to me coming from Tulsa.” Although he didn’t fully understand the characters – such as John Cleese’s BBC continuity announcer, with his catchphrase “And now for something completely different” – it didn’t matter. “It only added to the excitement,” Hader says. “There was something very exotic about it to me.”.

However much he loved Monty Python, though, it was filmmaking, rather than comedy, that initially drove the young Bill Hader. Long before he was one of the most ubiquitous comic actors of his generation, popping up in everything from Knocked Up to Trainwreck, Adventureland to Inside Out, he had designs on directing movies like those of Scorsese, Terrence Malick and Andrzej Wajda. After attending New York Film Academy in 1996, he spent a few unproductive semesters at the Art Institute of Phoenix and Scottsdale Community College, then dropped out and moved to LA in 1999. Starting at the bottom, he would persevere behind the scenes, directing a short film here, writing a screenplay there, but mostly working as a production assistant on movie sets. Acting was never something he truly considered, until a bad break-up prompted him to start taking classes at Second City LA, a school that specialised in improvisation and sketch comedy. He was good.