Royal Court theatre, London. A woman living in Gaza rehearses her evacuation drill, should an Israeli bomb fall on her family, in Khawla Ibraheem’s scalding one-woman play. If you had five to 15 minutes to flee your home before a bomb flattened it, what would you take? How would you get your family out of a seventh-floor flat? How fast could you run? These hypothetical questions take on chilling reality for a Palestinian woman living under Israeli occupation in Gaza. Khawla Ibraheem’s unnervingly funny (at first) and slowly searing monologue could not be more relevant, although it was first conceived in 2014. That it feels so urgent more than a decade on is all the more tragic.

![[Arifa Akbar]](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/uploads/2019/11/08/Arifa_Akbar.png?width=75&dpr=1&s=none&crop=none)

Developed and directed by Oliver Butler, who previously directed Heidi Schreck’s Pulitzer prize-nominated What the Constitution Means to Me, this too is delivered as a solo female testimony, whimsical at first, then throttling in its grip. Mariam (Ibraheem) is living with her elderly mother and young son in Gaza when war breaks out. The title is taken from the Israeli military protocol of forewarning civilians, five to 15 minutes before a bomb is dropped on their building, with a knock on their roof. Mariam imagines what this warning will mean: what if her child is asleep? What if her mother is in the shower? The principle of forewarning civilians within this timeframe has been debated in the recent Israel-Hamas conflict. This play shows us, woefully, what it means for Mariam.

Mariam begins rehearsing her evacuation drill playfully at first. She is psychologically terrorised by war but this is not apparent: she teases the audience, muses on marriage and motherhood. It is not far off standup but the tone imperceptibly slides into darkness until Miriam is trapped in her rehearsals, setting timers and training for the run of her life with weights representing her son. The drills, increasingly obsessive and interspersed with a fearful waiting, seem Beckettian in their existential terror.

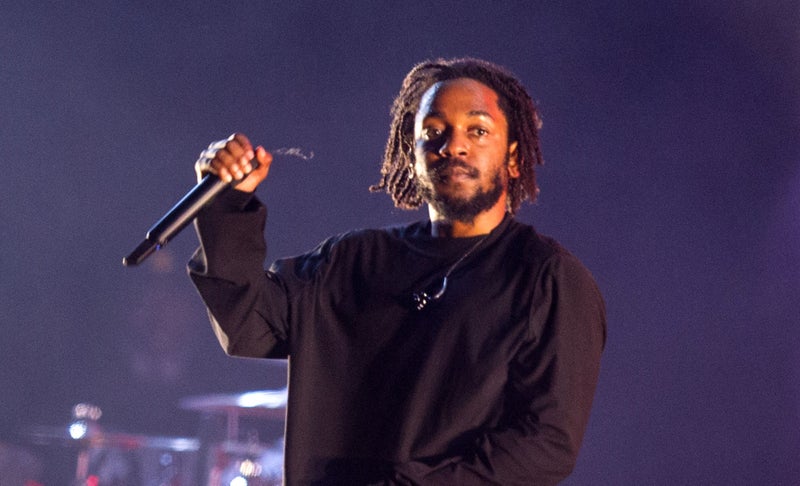

Ibraheem, a Syrian actor living under Israeli occupation in the Golan Heights, performs with such control, precision and truth that entire streets come to life. So does Mariam’s home, neighbours, and the weight of her son in her arms. In one abject moment, she describes children on the street who are play-acting a funeral procession and it sums up generational trauma in a single image.

There is only a chair on stage, as if the play itself can be packed away at short notice, while lighting, designed by Oona Curley, expands to fill the space along with Rami Nakhleh’s music and sound design. Like Schreck, Ibraheem focuses on the domestic and intimate but her story draws a much bigger picture of the indignities of occupation (the checkpoints, waiting for electricity, rushing to have a shower) and the terrifying plight of women strategising for the survival of their families in war. If a central purpose of theatre is to play out difficult conversations and breach divides, this devastating show is absolutely essential viewing.