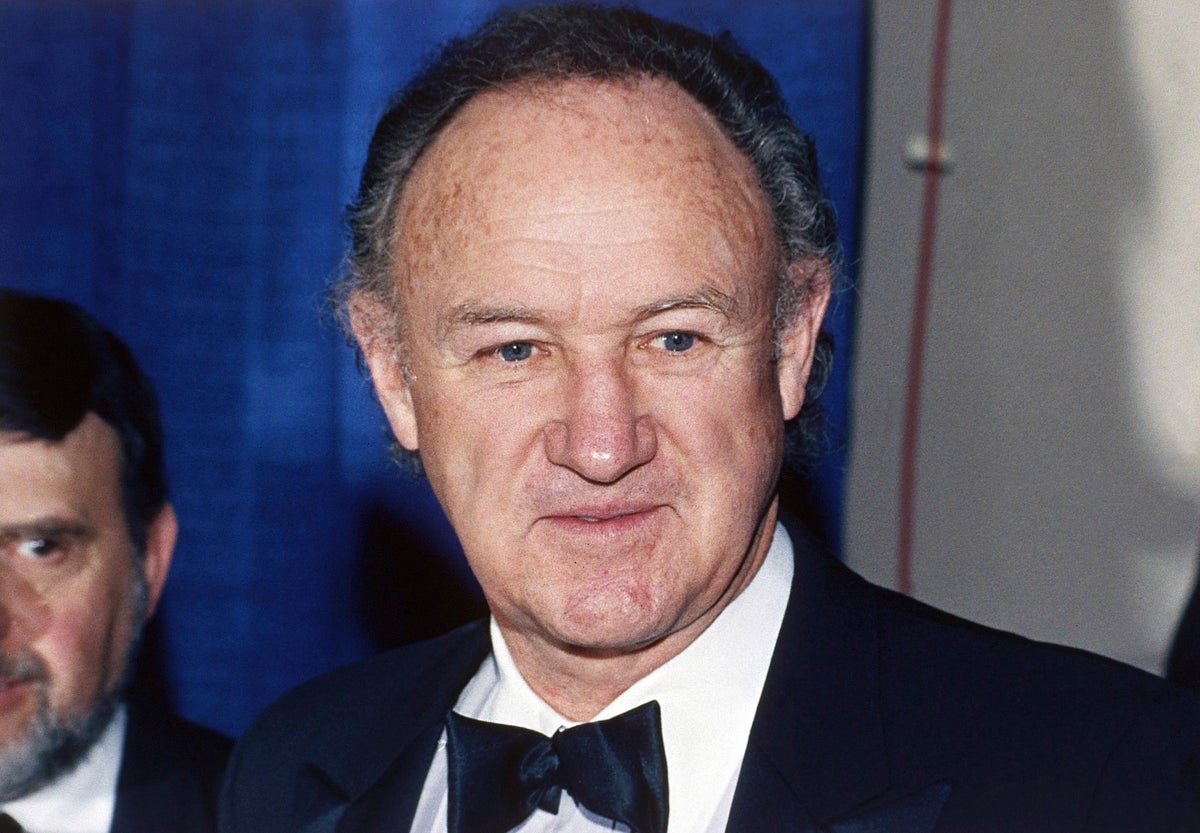

One of the greatest American actors of the 20th century was voted “least likely to succeed” by his first theater school, wasn’t a star until he was 40 and possessed a face he once described as “your everyday mineworker.”. Gene Hackman, a 6-foot-2 ex-Marine from Denville, Illinois, and a self-described “big lummox kind of person,” was as hard to define an actor as he was an unlikely star. “Everyman” was the most common label for Hackman, but even that seems to fall short for a performer capable of such volcanic intensity, such danger.

“He’s one of the ones who are willing to plunge their arm into the fire as far as it can go,’’ said Arthur Penn, who directed him in three films, including the one that earned Hackman his first Oscar nomination, “Bonnie and Clyde.”. Hackman was found dead alongside his wife, Betsy Arakawa, and their dog in their Santa Fe, New Mexico, home, authorities said Thursday. He was 95.

Hackman’s death, mourned across the film industry, renewed an old conundrum: How do you describe Gene Hackman? It was never one, easy-to-pinpoint thing that epitomized the actor. It was the totality of his live-wire screen presence. His characters were so real, you could have sworn they walked in right off the street.

Like Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle. Though one of Hackman’s defining roles, in William Friedkin’s “The French Connection,” Hackman initially recoiled from the character’s violence and racism. But in Hackman’s hands, Popeye Doyle was a gritty artifact of real life. Guys like this exist. Whether a character was sympathetic or not didn’t enter into it.

“That’s not important to me,” Hackman once said. “I want to make you believe this could be a human being.”. Across an incredible array of movies — “The Conversation,” “Night Moves,” The Poseidon Adventure,” “Mississippi Burning,” “Hoosiers,” “The Birdcage,” “The Royal Tenenbaums” — Hackman was, unfailingly, real. At the time of his death, it had been more than two decades since Hackman retired from acting. But time has done nothing to diminish the pugnacious rage, or the sweet sensitivity, of Hackman’s finest performances.

“American movies have always had certain kinds of self-styled actors who shouldn’t be stars but are,” Penn said. “Gene is in the company of Bogart, Tracy, and Cagney.”. That he seemed so comfortable far away from Hollywood only furthered the mythology of Hackman, who never showed even a little bit of interest in celebrity. In 2001, Hackman told The Los Angeles Times he wasn’t sure where his Oscar statues were. “Maybe they’re packed somewhere,” he said.

“If you look at yourself as a star you’ve already lost something in the portrayal of any human being,” Hackman told The New York Times in 1989. “I need to wear that hair shirt. I need to keep myself on the edge and keep as pure as possible.”.

The nature of that edge propelled Hackman through a blazing career that compressed movie star and character actor into one. Hackman sometimes spoke about the source of his drive. His father left when he was 13, departing with only a wave to his son who watched him go from a friend’s yard.

“It was a real adios,” Hackman told Vanity Fair. “It was so precise. Maybe that’s why I became an actor. I doubt I would have become so sensitive to human behavior if that hadn’t happened to me as a child — if I hadn’t realized how much one small gesture can mean.”.

Hackman’s youth was spent drifting. He quit high school after a blow-up with his basketball coach — an ironic beginning for an actor whose Norman Dale in “Hoosiers” is probably the quintessential hardwood mentor in movies. He joined the Marines at 16. He was a poor Marine, he said, who chafed at authority.

Years later when he was a doorman in New York, Hackman’s old drill instructor walked by and muttered that he was “a sorry son of a bitch.” Hackman resolved to redouble his efforts to make it as an actor. Maybe more than anything, he was fueled by an “I’ll show you” attitude.

“It was like me against them," Hackman later said, “and in some way, unfortunately, I still feel that way.”. Together with Robert Duvall and Dustin Hoffman (a friend from the Pasadena Playhouse, where their classmates named them both “least likely to succeed”), Hackman spent years working day jobs in New York while hustling for acting gigs.

“Our affectation was anti-establishment,” Hoffman said. “‘Making it’ meant staying pure, not selling out. ‘Making it’ meant doing the work.”. All of that living, coupled with Hackman’s resistance to anything peripheral, led to one of the great acting runs of the 1970s.

Foremost in that streak was Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Conversation” (1974). The role of surveillance expert Harry Caul, who overhears a murder, is unique in Hackman’s filmography. Coppola had first wanted Marlon Brando for the part, and you can understand why Hackman wouldn’t be your first instinct.